Banks the protected specis

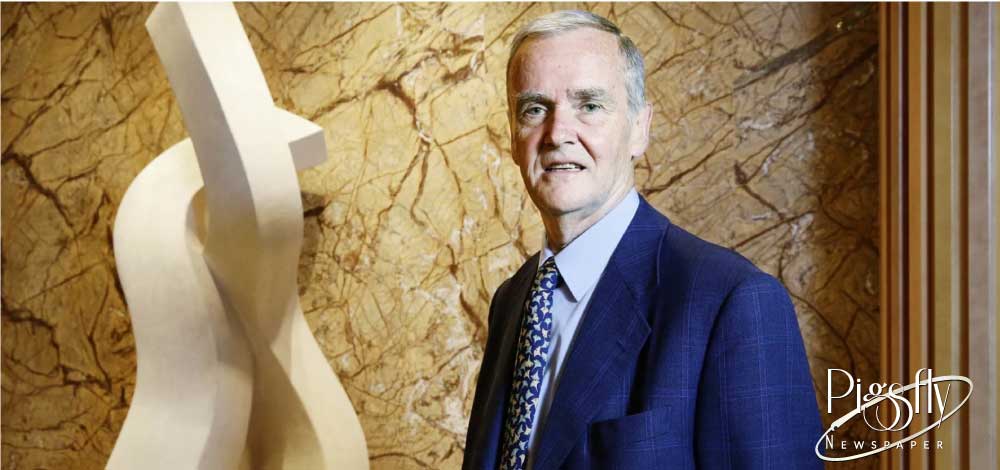

‘Protected species’: Former bank executive Rob Ferguson gives big four a serve

Which Bank - All Banks

Rob Ferguson’s CV reeks corporate establishment. He clocked 15 years at the top of one of Australia’s largest and most successful investment banks, BT, and two decades sitting around the boardroom tables of big-end-of-town companies including Westfield and GPT.

A University of Sydney alumni with degrees in economics and law and a career start in stockbroking round off his pedigree.

But Ferguson never really felt he was a member of the elite corporate club that dominated Australia during the 1980s and 1990s.

The seeds of his disrupter, even renegade, attitude appear to have been sown in his early years at BT Australia during the period the local banking industry was opened up to foreign competition.

The success the US-owned BT Australia achieved in carving out a large financial services business cemented Ferguson and his predecessor, Chris Corrigan, as challengers to the status quo.

Having hung up his business spurs last year when he resigned from the chairmanship of Primary Health Care (now Healius), Ferguson has left behind the last vestige of inhibition or political correctness and speaks openly on the economy, boards, the corporate regulator, auditors and in particular what he sees as the corporate equivalent of a ‘protected species’ – the big four banks.

Having been in the financial services industry but outside the five-pillar club, made up of AMP, the Commonwealth Bank, Westpac, ANZ and the National Australia Bank, Ferguson observed their behaviour over a long period – well before anyone was agitating for a royal commission. Banks provide an especially rich vein for discussion when he sits down with The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age.

As Ferguson sees it the royal commission crescendo was something the banks definitely deserved. They had it coming.

‘‘Yeah, absolutely they deserved to have it. I think the banks were arrogant, were out of touch, and all of that’s sort of been revealed by the process we’ve been through. So, I think it’s a fantastic process of calling them to task.’’

And Ferguson has little sympathy for those who run them.

And Ferguson has little sympathy for those who run them.

‘‘There’s a fundamental problem with banking in Australia, it’s so oligopolistic that the ability to earn super profits is like a sugar hit for the ego of the people that are running those organisations. They feel that they’re cleverer than they actually are.

‘‘That hubris shows up in lots of different things. It shows up in those organisations really not managing themselves properly. Because it’s sort of a license to print money at the big bank level, the big four level.’’

Ferguson’s view is that the protection afforded the banks by being too big to fail has also made them too big to manage.

Too big he thinks for the senior management and the boards to know what is going on multiple layers down in the organisation.

He argues that it’s not a matter of the directors of banks

not being fit for purpose rather that the organisation is not fit for purpose.

‘‘Because the banks are too big, too complicated. One of the expressions I use is that a bank – any company or any entity – should know pretty quickly if it’s stubbed its toe.

‘‘I think what happens with these banks, [is that] they’re so big that they stub their toe and it takes a year for the pain to come up to the organisation, and then it’s too late. The damage is done.’’

By this time what Ferguson describes as ‘gangrene’ has set because the people at the top couldn’t register the pain in real time.

National Australia Bank chairman Ken Henry was the biggest and most prized scalp of the post-royal commission search for responsibility.

In the corridors of big business there is division on Ken Henry. One view points to his arrogance and his tin ear to the seriousness of the banking industry’s culpability. The other sees him as a sacrificial lamb. Ferguson sits on the side of Henry’s supporters believing NAB’s former chairman spoke his mind, rather than followed political correctness.

In that sense, at least, Henry and Ferguson appear to be kindred spirits.

‘‘I felt great sympathy for Ken because I felt he was thinking out loud and he was made an example of.

‘‘He’s not your conventional businessman. He wasn’t being political and toeing the line. It’s a body on the tarmac in these environments…’’

But Ferguson’s sympathy doesn’t extend to banks at large.

‘‘I think they’ve abused their social licence in the sense that they’ve gone for profit rather than recognising the privilege that they have. To have the privilege of lender of last resort protection is just an enormous privilege, which means that they earn super profits. I think that organisations that earn economic rents are prime – and are fundamental to the system just as electricity and gas and water is.

‘‘The financial system and the banking system is just as fundamental. We expect it to work, we need it to work, the place grinds to a halt if it doesn’t. To have the people running those organisations not having the sense of responsibility that other regulated utilities have, I think that’s a bad thing,’’ he says.

Despite having sat on the board of several large companies, Ferguson’s hot button issues often mirror those of the broader community – not just his opinions on banks but on corporations in general.

It is rare to find a current or former board director who is openly critical of the excesses of executive pay. It’s rare to find one that even concedes that there is an excess.

For Ferguson the drift towards overpaying management folds neatly into his broader theory on gatekeeper conflicts of interest. In this respect Ferguson also singles out auditors for being unwilling to take corporates to task for fear of ‘‘biting the hand that feeds them’’.

‘‘The mechanism for paying chief executives is flawed by the fact that boards – I don’t think they’re tough enough in terms of compensation.’’

The well-worn argument that big salaries are needed to attract executives in a competitive market doesn’t wash with Ferguson.

‘‘To me, that’s just a thoroughly lazy argument. In a way, their [board’s] bread is buttered by management as well. Management make them comfortable; they take them on trips to America and to visit plants and all this sort of stuff, which is all fine to do.

‘‘But I think amongst boards, there tends to be a ‘let’s not rock the boat’ thing on the compensation thing, …. after all, it’s not the board’s money it’s the shareholder’s money. You’re asking somebody to be tough when their inclination is not to because it’s easier just to [say], oh, well, we’re just paying the market. It’s all too hard.’’

It seems a curious stance given Ferguson’s former membership of the Westfield board whose executives were renowned for the generous size of their pay packets.

It seems a curious stance given Ferguson’s former membership of the Westfield board whose executives were renowned for the generous size of their pay packets.

He agrees the executive team at the shopping centre group, at various times dominated by the Lowy family, were highly paid but said the performance justified the salaries.

‘‘They [the salaries] were [large] but ….. how do you work out what to pay them when you look at the spectacular returns that the shareholders got? ‘‘I don’t t think the shareholders whinged. I think the proxy advisors whinged and the amounts were large.’’ In many respects while Westfield was not a governance star, given it was run more like a large family company, its performance for many years (and in the years when Ferguson was a director) was stellar.

But Ferguson was not averse to accepting a corporate challenge. It was in the dying days of the global financial crisis that Ferguson joined the board of thenfinancially-troubled property group GPT.

Last year, after nearly a decade in the chair, it was during his farewell shareholder meeting that he regaled attendees with a few hair-raising anecdotes about the process of being invited to join the board of the property group which at that stage had no chief executive and was in desperate need of capital.

The mayday call came from fellow BT alumni Ian Martin, who wanted Ferguson to become a director.

‘‘You’ve got to be joking, you’ve got issues with your balance sheet that need to be fixed before anyone would look at the board idea,’’ he told Martin who had, rather unluckily, joined GPT’s board a few years earlier, according to press reports of the meeting.

Ferguson told shareholders that a few months later Martin approached him again reporting the news that a chief executive had been found and equity had been raised.

An agreement was reached that Ferguson would become chairman of GPT within a year – on the proviso that ‘‘he behaved’’.

It would seem that Ferguson’s penchant for being outspoken preceded his retirement from the corporate community.

Not fair? why judges have been accused of failing Australian consumers

When a judge says a bank’s borrowers could afford its loans if they cut down on Wagyu beef and fine shiraz, the accusation that the judiciary is out of touch is not a hard one to make.

When a judge says a bank’s borrowers could afford its loans if they cut down on Wagyu beef and fine shiraz, the accusation that the judiciary is out of touch is not a hard one to make.

That was the case last month, when the federal court judge Nye Perram threw out a case brought by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission alleging irresponsible home lending by Westpac.

Consumer groups exploded, and the ruling went down badly with a regulator that had been told by the banking royal commissioner, Kenneth Hayne – himself a former high court judge – to be quicker to resort to the courts.

But it was only one of a series of cases over the past few years, dealing with everything from door-to-door vacuum cleaner salesman to health insurance, in which judges have frustrated attempts by regulators to use existing laws to protect consumers.

Now Australia’s consumer regulator has called for the law to be changed to bar companies acting unfairly towards customers, after a series of court rulings that have raised concerns judges are out of touch with community expectations.

Rod Sims, the chairman of the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, told the Guardian a new “unfair conduct” provision should apply across the economy and replace current provisions outlawing “unconscionable conduct” – a phrase rooted in the ancient law of equity that has been criticised because it brings with it connotations of deliberate wrongdoing.

His call adds weight to similar demands from regulators, judges and consumer groups who say the way the courts interpret the existing law is too narrow.

Even when regulators do win under current laws banning unfair contracts, as the ACCC did on Wednesday in a case against the hair clinic Ashley & Martin, the most that can happen is that the arrangement in question is set aside – judges cannot levy fines for breaches.

The Kobelt case

Frustration with judges among regulators came to a head in June, when Asic lost a high court case in which it alleged a man named Lindsay Kobelt engaged in unconscionable conduct in the way he gave credit to customers of a store he ran in an Aboriginal community in remote South Australia.

The facts of the way the “book-up” scheme operated, as found by the court, seem shocking: Kobelt advanced credit to his customers in return for custody of their bank keycards and their PINs.

Most of the credit was advanced to buy cars that had often done more than 200,000 kilometres – vehicles for which Kobelt charged a hefty mark-up in return for the loan.

When the customer’s wages or Centrelink payments arrived, Kobelt or one of his employees drained the account of all or nearly all of the money.

His records of who owed what were cramped, chaotic and barely legible – so badly kept that customers would have had considerable difficulty understanding the entries.

The case divided the court four to three, with the majority ruling that it suited Kobelt’s customers to allow him to drain their bank accounts and he did not exploit them or take advantage of their lack of financial literacy.

It was as if the judges thought buying a car through book-up was “the same as buying a tub of olives at South Melbourne market”, one experienced regulator told Guardian Australia.

Consumer groups also heavily criticised the decision, with the Consumer Action Law Centre saying it showed the law was not working to protect customers and calling for the rules to be changed.

One of Victoria’s most senior judges, the president of the court of appeal, Chris Maxwell, also took aim at the decision last month, saying he would have decided the case differently.

In a speech to the legal community, Maxwell traced the history of unconscionable conduct all the way back to the courts of equity set up in the 15th century and pointed out that proving it generally relied on showing “that the stronger party had knowledge, or at least exhibited wilful ignorance, of the weaker party’s disability”.

And he drew from the dissent written by one of the three judges in the minority in the Kobelt case, James Edelman, to point out that over the past few decades parliament had repeatedly tried to expand the definition of unconscionable conduct “in continued efforts to require courts to take a less restrictive approach”.

He asked: “Are the courts still being too restrictive? Or is the problem with the standard?

“It would certainly promote better understanding by all concerned – and, it might be hoped, higher standards of conduct – if we had a prohibition on conduct which was ‘in all the circumstances unfair’,” he said.

‘Change the test’

Sims says Maxwell’s speech and Edelman’s dissent “have helped clarify my personal thinking and I think the thinking of other people in the ACCC.

“I don’t think this is a matter of criticising judges at all, I think it’s a matter of now we’ve clearly got an issue,” he says. “It’s up to the legislature to be clear about what they mean, and if what they mean is unfairness, which I think they do, then we should change the test to that.”

He says he has also considered the problem in light of efforts to make banks behave better following the Hayne royal commission. “If you want to make banks act fairly, why not just make that the law,” he says.

While Sims is careful not to criticise the judiciary, others are more forthright.

In an article published this month in the Journal of Equity, three legal academics – Melbourne law school professors Jeannie Marie Paterson and Elise Bant, with student Matthew Clare – said the majority in Kobelt took an “unduly narrow” view of the law and their ruling would make it more difficult to pursue companies over business practices that hurt consumers.

The majority failed to consider that Kobelt’s book-up system broke credit laws or “squarely investigate the community or cultural values that were said to justify the business model operating in a remote Indigenous community,” the academics said.

The former Asic deputy chairman Peter Kell, who appeared before the royal commission while at the financial regulator, supports Sims’s call for a new law against unfair conduct.

“I think we now have enough cases on the books that we can safely say the unconscionable conduct provision sets the bar too high when it comes to bad market conduct,” he says.

“In particular, it sets the bar too high when it comes to conduct that harms the most vulnerable members of our community.”

The Consumer Action Law Centre has used its submission to a treasury review of the ACCC’s digital platforms inquiry to call for an economy-wide law against unfair conduct.

“The operation of the free market in Australia has failed to deliver fair outcomes,” the centre said in the submission.

It criticised the high court majority in Kobelt for failing to heed parliament’s attempts to broaden the concept of unconscionable conduct and for focusing on the conduct of Kobelt, rather than the effect on his customers.

“Not only is it a problem that the courts have read the existing provision too narrowly, it is a problem of the term ‘unconscionable’ itself,” the centre said. “Replacing it with fairness will encourage businesses to consider the impact of their conduct on consumers and can thus play a role in contributing to cultural change in Australian industry.”

While it was an Asic case that has crystallised the new push for laws against unfair conduct, the current Asic commissioner responsible for enforcement, Daniel Crennan QC, will not be drawn on whether he supports the move, saying it is a matter for the government.

However, he points out that the courts will have to consider the idea of fairness more often anyway because of a change to the law designed to crack down on bad behaviour in the finance sector.

Courts can now fine licensed finance companies if they fail to act “fairly, honestly and efficiently” towards customers.

“Fairness will be tested by us, the regulators, in the courts in coming years,” he says. “That may well be helpful to the debate.”