Economic Response to the Coronavirus

In this video Australian PM Scott Morrison speaks to reporters in Canberra, outlining initial measures of a $17.6bn package as part of a federal government plan to keep the economy afloat amid the coronavirus pandemic

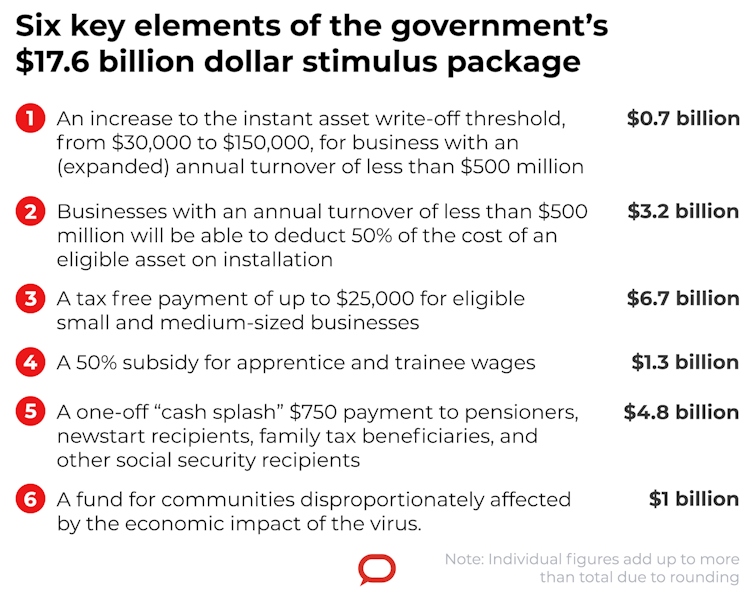

The Australian Government has announced an economic response totalling $17.6 billion across the forward estimates to protect the economy by maintaining confidence, supporting investment and keeping people in jobs. Additional household income and business support will flow through to strengthen the wider economy.

Morrison's package

The package has two primary aims. One is to ensure that spending and production don’t shrink in the June quarter after shrinking in the March quarter, triggering what, for better or worse, people call a technical recession.

Morrison’s coronavirus package is a good start, but he’ll probably have to spend more

Peter Martin, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

What makes the prime minister confident most households will spend A$750 delivered in cash, when they mostly wouldn’t spend the A$1,080 delivered in the form of bonus tax refunds after last year’s budget?

Experience.

Here’s how he put it on Thursday, announcing the economic response to the coronavirus:

Australians will be getting a cheque for $750. Now it’s not for us to tell those Australians how to spend their money, but what we do know from experience is that they will spend that money, and that money will encourage economic activity.

That experience was Labor’s.

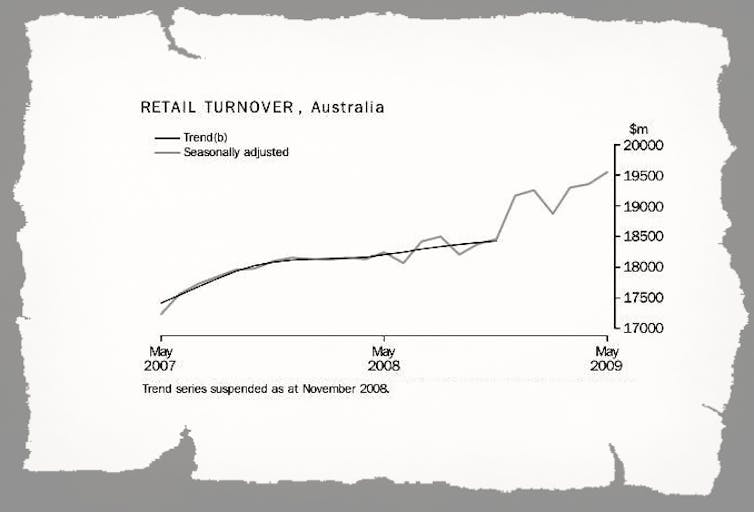

On October 11, 2008, Labor announced cash payments totalling between $1,000 and $1,400 per eligible household to stave off a retail recession.

It offered still more in February 2009.

Read more:

The coronavirus stimulus program is Labor’s in disguise, as it should be

The first cheques went out in December. Spending surged 4% that month after scarcely growing all year. A year on, spending was 5.4% higher than before the cheques went out.

In Japan, the United States, Canada and Germany where stimulus packages were not targeted at consumers, retail spending slipped by 2-3%. In Australia, it surged 5%.

So big was the effect that the payments were staggered by region to ensure cash delivery trucks could top up the automatic teller machines first.

The statisticians collecting retail sales data at the Bureau of Statistics abandoned their usual practice and stopped drawing a trend line.

The jump was impossible to reconcile with the pre-existing trend.

The Treasury had searched the economic literature and determined that cash payments were more likely to be spent than tax cuts, and could be delivered much more quickly.

Six million Australians receive government benefits of some sort, whether they think of themselves as on welfare or not. As recipients of family allowance, childcare support, the pension or even the seniors health card, they are on Centrelink’s books. (Centrelink recently changed its name to Services Australia.)

The payment machine that delivered robodebt can just as easily deliver “robocheques”.

Read more:

Cash handout of $750 for 6.5 million pensioners and others receiving government payments

Treasury Secretary Steven Kennedy, who advised Prime Minister Scott Morrison and Treasurer Josh Frydenberg to give households cash this time instead of tax refunds, saw the effect at first hand. He was working in Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s office as the good news came through.

If there is an important criticism of the Morrison government’s (first) coronavirus stimulus package, it would be that it doesn’t concentrate on households enough.

Household spending accounts for 55% of Australia’s gross domestic product, yet payments directed to households make up only 27% of the $17.6 billion the government is spending.

The package has two primary aims. One is to ensure that spending and production don’t shrink in the June quarter after shrinking in the March quarter, triggering what, for better or worse, people call a technical recession.

The Treasury expects it to boost economic activity by 1.5% in the June quarter.

If it does, it should be enough to compensate for the downturn we would have without it, always remembering that we don’t yet know how bad things will get in the three months to June – how many schools and public gathering places will be closed, and how many workers will have to stay home to care for children who can’t go to school or family members who are ill.

Read more:

When it comes to sick leave, we’re not much better prepared for coronavirus than the US

The second aim is to stop the unemployment rate climbing. When it climbs more than a few points it tends to keep going. In the early 1990s recession it climbed from 6% to 10% in a matter of months.

People who entered the labour force and couldn’t get work were scarred for years.

Labor’s most enduring achievement during the global financial crisis in 2008 and 2009 was to stop unemployment climbing above 6%.

That’s what the government’s $11.8 billion of payments to businesses are aimed at, whether delivered in the form of a boosted instant asset writeoff (available only until June 30), accelerated depreciation, payments to cover salaries, or wage assistance for apprentices and trainees.

Morrison wants businesses in the best possible position to hold onto their workers. He wants them to display “patriotism”.![]()

Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Grattan on Friday: Will many people be too worried to spend the cash splashed their way?

Michelle Grattan, University of Canberra

Let’s hope it won’t come to this, but handling the coronavirus might eventually make dealing with the global financial crisis look rather a doddle.

The GFC was devastating – for businesses, individuals and many economies. But it was a financial crisis that drove an economic crisis. When a health crisis is the driver of an economic crisis, the uncertainties are multiplied, and people’s reactions are more difficult to predict.

Will the government’s mega $17.6 billion stimulus package be sufficiently big and well targeted to head off an Australian recession? That was the obvious question when on Thursday Scott Morrison had to eat many of his previous words about Labor’s alleged waywardness in times past and announce his own cash splash for individuals and businesses.

Read more:

Big stimulus package to splash cash, including $25,000 to small and medium-sized businesses

It’s easy to ask but no one can be confident about the answer.

The spending has been carefully pitched to try to stop the economy tanking via a negative June quarter (the general assumption is the March one is down the gurgler). Some $11 billion will go out the door by June 30, and it is estimated the measures will add 1.5% to growth in the June quarter. The rub is, no one knows how much the virus will take off growth in that quarter.

One pressing uncertainty is whether there’ll be a shutdown of major events. So far, the medical advice has been that mass gatherings should not be abandoned.

Scott Morrison told reporters he was looking forward to attending the football this weekend. But many organisations are cancelling smaller events, ranging from the school fete to the business conference. Government House in Canberra has pulled its weekend open day.

There’s an increasing prospect large gatherings will have to be stopped, something primarily in state governments’ hands.

Former Labor leader Bill Shorten on Thursday suggested this should come sooner rather than later. “This is going to be a major policy question, not in weeks and months, but in days. Do we keep having big events? Will we teach school from home?” he said on Sky.

“But we’ve got to have more social distancing. And that is the only way to stop this pandemic being worse than it might otherwise be,” he said.

A pattern is emerging overseas. In the United States the National Basketball Association (NBA) has suspended its season after a player tested positive, and many sporting and other activities around the world are being called off.

The cancelling of events, whether after official decrees or by the actions of individual organisations, will hit the economy hard, but the impact must be near impossible to predict.

In any crisis, confidence is key. In this crisis, people obviously are worried not just about jobs and income but also about the sickness.

Different segments of the population will vary in their principal concerns. Young people will be more preoccupied with the employment and financial implications, older people with health matters, but there will be much overlap, with many of the young and middle aged fretting about older relatives.

Glitches will be found and priorities disputed but in general the government’s package appears sound. Nearly $12 billion goes to business, largely to small and medium sized enterprises, in an attempt to keep people in jobs. Meanwhile Morrison is putting moral pressure on big businesses to look after their own. Some are responding.

The $4.8 billion for 6.5 million welfare recipients and other lower income people to receive a one-off $750 payment is unashamedly designed to boost household consumption ASAP. The government can’t wait to get the money out – it will be dispatched from the end of this month.

Here, however, more uncertainties emerge. All the economic data and past experiences say giving these people money will see it spent rather than saved. But will things be the same in these extraordinary circumstances?

About half the beneficiaries of this cash are pensioners – people in the coronavirus’ most vulnerable age group. How many of them will be fearful enough about their health prospects to think they should put away some or all of their windfall from the government?

In political terms, there are lessons in the unfolding crisis.

Politicians should remember that old adage of what goes around, comes around. The Coalition in recent years has made a mantra of how the Rudd government spent too much on combatting the impact of the GFC.

There’s an argument that Labor overspent in its second stimulus package, costing $42 billion, and we know it had flaws. But it was better to err on the side of overkill, and now it’s Kevin Rudd and former treasurer Wayne Swan running round finger pointing.

Read more:

The coronavirus stimulus program is Labor’s in disguise, as it should be

The Morrison government is aware of the danger of doing too little, hence as it crafted the measures it “grew” the package (which compares with Rudd’s $10.4 billion first tranche). And it stresses the plan is “scalable” – an ugly way of promising to do more if necessary. The next opportunity will be in the May budget.

It’s the same with the government’s crowing about the (prospective) surplus while this was still in the budget’s womb. It will be born a deficit.

Politicians never seem to learn it’s best not to get too full of yourself.

On Thursday night Morrison took the rare course of an address to the nation. He wanted to reassure the public. But are people comforted these days by anything a political leader says? In our age of distrust of the political class, probably not much. Perhaps better to put the Chief Medical Officer on.

Commentators have been saying this crisis will make or break Morrison. We can’t be sure about this either.

If the economy goes into a serious recession, that would transform the political landscape, but in what way is another unknown. A recession helped see off the Fraser government. But as treasurer Paul Keating announced “the recession we had to have” at the start of the 1990s and then as prime minister he won an election in 1993.

So a recession wouldn’t necessarily be fatal for the Morrison government. Nor would avoiding one necessarily deliver the Prime Minister the votes of a thankful electorate.

The public were not grateful to Labor for warding off recession. Gratitude isn’t something today’s fractious voters are inclined to hand out. They thought it was Labor’s job to get them through the GFC. If the Coalition prevents a recession Morrison will receive some bouquets, but whether their pleasant scent lingered would depend on a whole lot else.

Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.