Why is the government ignoring expert advice on Covid?

There is an old joke about the global search for a one-armed economist, because when asked for an opinion the answer is often, “on the one hand … and then on the other”. It is also said that if you laid all the economists in the world end to end, you would still never reach a conclusion.

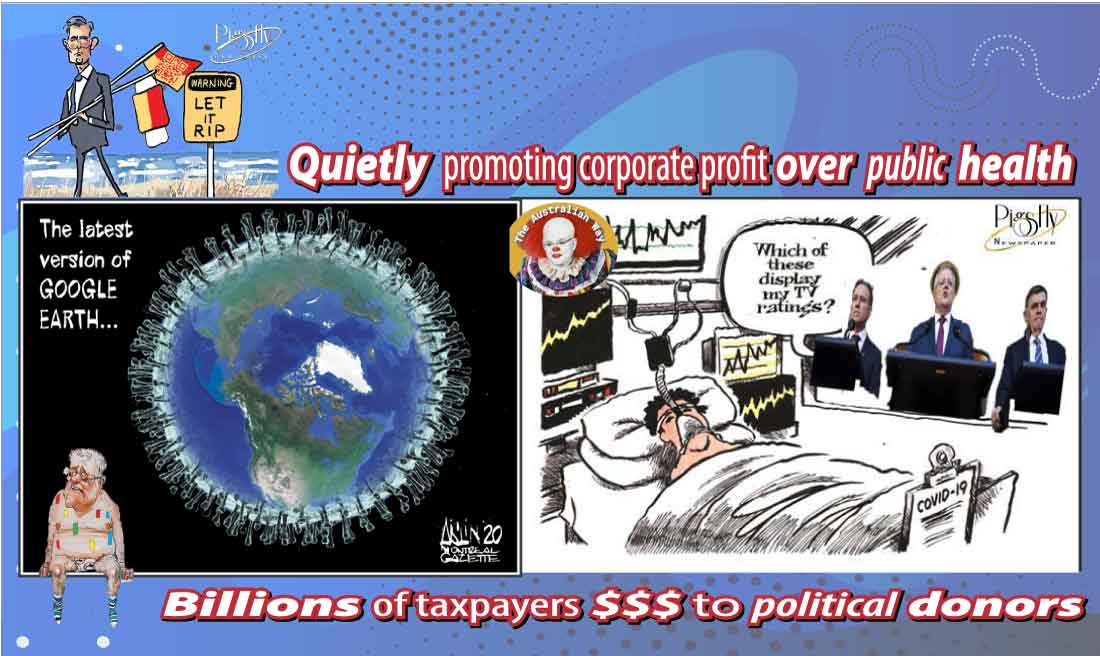

True enough for economists, but what about for epidemiologists? Governments globally claim to base their policy responses to Covid-19 on science, on the advice of medical experts. But there has been a multiplicity of different opinions on the evidence, allowing governments to be politically selective in deciding what to do – even to ignore the basic thrust of the advice.

The situation is further complicated here in Australia, with each state having a chief medical officer and Health minister, on top of both at the federal level. So, who to believe? As time has gone on, with the states essentially driving the policy responses, state leaders have become more concerned about their regions and political challenges than about national considerations.

Now is not the time for political timidity. To ignore the realities of the pandemic and the medical advice may ultimately seriously constrain the budget position, including essential health, hospital and aged-care reforms.

A particular difficulty for those giving advice initially was that the only significant historical experience on which they could draw – apart perhaps from the less pervasive experiences with SARS, MERS, Ebola and the like – was the 1918 influenza pandemic. They lacked clear imperatives for today’s modelling. In reality, the medical and government responses to the pandemic were essentially “learning by doing”, loosely based on some scientific and medical opinions. Politicians had too much leeway for interpretation, and in some cases politics clearly took over. I recall Scott Morrison’s first announcement of a size limit on outdoor gatherings, which he claimed could be delayed until the following Monday, allowing two events of significance to him personally – a Sharks NRL game and a Hillsong convention – to take place over that weekend. It’s hard to accept that the delay was based on medical advice rather than political expediency.

More recently, messages have been inconsistent in relation to mask wearing, an issue that unfortunately has been weaponised. In the United States, it has divided Republicans and Democrats, state by state, even though most medical advice was along the lines that masks should be an essential part of the policy response to deal with a highly infectious, airborne virus.

Here in recent days, with the mounting case numbers and deaths from the more infectious and transmissible subvariants of Omicron, the issues of mask wearing and working from home have emerged again.

Controversy is raging. Since mid-December we had been led to believe that the worst was over and we were now “living with Covid”. The premature relaxation of many health restrictions was again driven by politics: the desire to claim that we could all have our “freedoms” back to ensure an enjoyable Christmas, en route to the May election. Making commonsense recommendations such as mask wearing into a “freedom issue” – along with the fearmongering hints of drift to “totalitarianism” or “autocracy” – were, quite frankly, ridiculous.

The recent announcement by Victorian Health Minister Mary-Anne Thomas that she will oppose mask mandates reflects concern about the consequences for her government of the “freedom” movement in the run-up to the state election. Her acknowledgement that mandates had been recommended reflects medical advice but begs the question of why her government hasn’t been consistently and clearly messaging the significant role of masks. Queensland ministers have been making similar utterances. Medical advice needs to be effectively and authoritatively communicated – over and above statements by politicians – to the broader public. This becomes an imperative if the politics favours allowing personal choice in matters such as mask wearing. Obviously the public needs reliable, objective, effectively communicated information if indeed we are left to decide for ourselves and our communities.

In the course of this week we have heard federal chief medical officer Paul Kelly warn – publicly and to the national cabinet and to a meeting of Health ministers – that the current wave is rivalling the January peak, that in terms of infectiousness this subvariant of the virus is “more like measles than it is like flu”. Yet he stumbled as to whether he actually recommended a return to mandates, clearly suggesting that the politicians hadn’t taken his advice.

People need to know the details of the infection rates and deaths. Whatever happened to the daily briefings, reporting new case numbers, hospitalisations and deaths? People are also keen to know details of just how long vaccinations are likely to be effective, and of the reinfection rates, having been told that vaccinations and previous Covid-19 infections reduced the chances of infection and reinfection. What about long Covid? Not only does the public need to know such details, the public has a right to know. This fact seems to have been conveniently forgotten.

In a recent interview with Patricia Karvelas on the ABC, new federal Health minister Mark Butler tried to shift the nature of the debate, in light of the new wave of infections. He made sensible comments concerning the public’s desire to move beyond “community-wide” government orders and mandates to “more targeted mandates” to protect the most vulnerable, those in aged care and hospital facilities, and in “high transmission” areas such as public transport, in addition to programs focused on reducing severe illness.

But the government flip-flopped on the issue of pandemic leave disaster payments, which are designed to reduce the scope of transmission, by assisting those who are not covered by sick leave to stay home from work and isolate.

This was always designed as a temporary payment by the previous government, which set a termination date of June 30. However, in the context of the new wave, pressure was placed on the Albanese government by the Opposition, medical professionals and indeed some of their own parliamentary members to extend the payments.

The pandemic numbers should be alarming. In 2020 the pandemic peaked in August, recording up to 715 cases in a day, 680 people in hospital and 20 deaths. Recently, we have been recording far worse numbers – approaching 55,000 daily cases, with more than 5000 in hospital and 88 deaths reported in Thursday’s figures.

The government’s response has been complicated, as it has sought to link it to the need for budget repair, initially refusing to sustain these payments as they would essentially be funded by even more “borrowed money”. Of course, this doesn’t have to be the case. Savings could be made in other spending programs or funds raised by tax increases, both of which the government has so far resisted. But both will need to be the essence of budget repair in the longer term. It comes down to a question of priorities, and it will be an important challenge for this government, especially given their oft-repeated commitment to ensure that “nobody is left behind”.

The challenge of spending priorities is very real. There are many worthy projects over and above emergency relief, given the structural weaknesses that the pandemic has exposed, especially in the area of health and aged care, and they can’t be left to drift further. The Albanese government must address how it balances the need for continuing emergency support in this rolling pandemic with the need to get the budget on a sustainable footing. Surely it is better in this situation to take the people into your confidence, to lay out the detail of the unfolding virus situation, to be honest about whether or not mandates are required and so on.

The initial medical and economic responses to the pandemic called for restrictions and (personal) financial support.

Overall there was a reasonable degree of bipartisanship in this difficult process. Now is not the time for political timidity. To ignore the realities of the pandemic and the medical advice may ultimately seriously constrain the budget position, including essential health, hospital and aged-care reforms, and perhaps others such as defence spending, at the most inopportune time.

The pandemic will be with us for some time yet, constantly emphasising the structural inadequacies of our health and hospital systems.

The question has to be asked: is it an adequate response to leave decisions about masks and working from home to individuals and businesses, especially when the medical advice is so strong? Surely in such circumstances, there is a clear responsibility for government to lead, irrespective of the feared electoral consequences? Of course, this would require the government to explain and educate.

If there was a clear message from the last federal election, as trite as it may seem to some, it is that voters want their political representatives to represent their interests to the benefit of the nation. Most would now see the urgent national need for leadership on how best to respond to the latest manifestation of the virus. Most have accepted the need for vaccinations and boosters, and would accept that masks are an important response to contain infection and transmission, to protect the health of their family, friends and communities.

Our economic outlook and wellbeing depend crucially on the virus’s behaviour, and we assume the basic medical advice hasn’t changed, although the politics have, with a new federal government and two state elections on the horizon.

Politicians have become squeamish about broad-based mandates and funding assistance. They are desperately trying to carve out an effective, fair and affordable response to yet another new wave and probably more mutations to come.

John Hewson originally published this article

John Hewson is a professor at the ANU Crawford School of Public Policy and former Liberal opposition leader.

This article was first published in the print edition of The Saturday Paper on July 23, 2022 as “When politics meets science”.