Protected species

Government agrees to national anti-corruption body – with strict limits

Government agrees to national anti-corruption body – with strict limits

Michelle Grattan, University of Canberra

The government has given in to pressure to set up a new Commonwealth Integrity Commission but its operation would be strictly circumscribed, without the ability to hold public hearings into allegations of corruption against politicians.

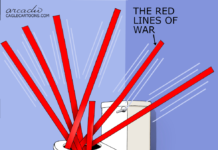

While the new organisation would be the lead body in Australia’s multi-agency anti-corruption framework, Scott Morrison stressed the government had learned the lessons of “failed experiments” at state level.

“I have no interest in establishing kangaroo courts that, frankly, have been used, sadly, too often for the pursuit of political, commercial or bureaucratic agendas in the public space”, he told a joint news conference with Attorney-General Christian Porter.

The announcement comes after crossbench pressure in the final sitting of parliament for a new federal anti-corruption body, which had earlier been promised by the opposition. Morrison said the government had been working on the issue since January.

Read more:

View from The Hill: Day One of minority government sees battle over national integrity commission

Opposition leader Bill Shorten slammed the proposed body as “not a fair dinkum anti-corruption commission”. It would be limited in scope and power and have no transparency.

Also – given it would not be able to investigate matters retrospectively – “Mr Morrison should explain to the Australian people why he wants to set up a national anti-corruption commission which curiously exempts himself and the current government from any

scrutiny”.

Morrison and Porter said in a statement that the CIC, an independent statutory agency, would be headed by a commissioner and two deputy commissioners, and have public sector and law enforcement integrity divisions.

“The public sector integrity division will cover departments, agencies and their staff, parliamentarians, and their staff, staff of federal judicial officers, and subject to consultation judicial officers themselves, as well as contractors.”

The Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity would be reconstituted as the law enforcement integrity division. It would have an expanded jurisdiction to also include the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, the Australian Prudential Regulation

Authority, the Australian Securities and Investment, the Australian Taxation Office, and the whole of the Agriculture Department.

Both divisions would investigate allegations of criminal corruption. The criminal law would be amended to add new corruption offences.

The CIC would have the power to conduct public hearings only through its law enforcement division.

The public sector integrity division would not be able to make public findings but would investigate potential criminal conduct and refer matters to the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions.

The government outline of its proposed operation says “it will only investigate criminal offences, and will not make findings of corruption at large.

“It will not make findings of corruption (or other criminal offending). Findings of corruption will be a matter for the courts to determine, according to the relevant criminal offence. This addresses one of the key flaws in various state anti-corruption bodies, being that findings of corruption can be made at large without having to follow fundamental justice processes.”

The CIC’s investigatory role is to “complement” the work of the Australian federal Police. “The AFP will retain its role in investigating criminal corruption outside of the public sector, and could cooperate with or take over investigations on referral by the CIC where appropriate”.

The public sector division “will focus on the investigation of serious or systemic corrupt conduct, rather than looking into issues of misconduct or non-compliance under various codes of conduct”.

Independent Andrew Wilkie said the proposal was “fundamentally flawed and entirely unacceptable.”

“For example the public sector integrity division, which will investigate parliamentarians and their staff, can only investigate a specific set of criminal offences and can’t make findings of corruption, which is just bizarre.

“Moreover an MP can only be referred by a particular agency and there’s no way for the public to refer someone – and there’ll be no public hearings at all meaning the Commission will operate behind closed doors”.

“Moreover an MP can only be referred by a particular agency and there’s no way for the public to refer someone – and there’ll be no public hearings at all meaning the Commission will operate behind closed doors”.

Crossbencher Kerry Phelps tweeted “I can’t speak for the entire crossbench but I certainly won’t be supporting any proposal that fails to result in adequate transparency and proper investigative powers”.![]()

Michelle Grattan, Professorial Fellow, University of Canberra

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Federal MPs, their staff and public servants will be breathing a sigh of relief with Scott Morrison’s release of the broad details of Australia’s first national anticorruption agency.

While the announcement of the Commonwealth Integrity Commission is welcome and overdue, the decision to restrict its powers to ensure MPs and their staff will not face public hearings or be placed under arrest is bewildering and unnecessary.

The consultation paper released on Thursday effectively creates a class of public servant which the government believes is more likely to be corrupt and, therefore, should be subject to greater investigative powers.

This means those working for the Australian Federal Police, Australian Securities and Investment Commission, the Australian Tax Office, Border Force and Biosecurity Australia could be hauled before public hearings, be placed under arrest and have their communications intercepted. All of this fine. It’s what anti-corruption agencies are expected to do. But what’s not fine is the government’s decision go soft on parliamentarians, their staff and non-law enforcement public servants.

They won’t face public hearings. They won’t be placed under arrest. The CIC will also not be able to make any findings of corrupt conduct; this will be left to the courts.

The government remains undecided on whether the public service division covering MPs will be able to intercept phone calls and the like. Surely, these are necessary tools to root out corruption?

It seems the fear campaign about the operations of NSW’s Independent Commission Against Corruption is reflected in the government’s preferred model. For instance, the new CIC will not be able to act on a complaint about a MP from a member of the public.

This is problematic. What if a member of the public had specific evidence of a MP or a member of their family accepting shares in a company in return for a beneficial decision? How is the public interest served by the CIC not being able to act on this information?

The government has defended its decision to have a split CIC on the basis that people working in law enforcement agencies with access to coercive powers and sensitive databases also know better than most how to conceal corrupt behaviour.

While this may be true, it is not a sufficient reason to apply a softer touch to and far more limited oversight of other public servants, including MPs and their staff.

The Morrison CIC will not be geared to examine codes of conduct or ethical breaches unless they appear to be significant criminal breaches. This may not be a bad thing as existing agencies such as the Ombudsman, the Public Service Commissioner and parliamentary committees can handle lower level matters.

The Morrison model does have some positives.

One is the creation of a criminal offence for a failure to report public sector corruption.

This means senior public servants cannot sweep things under the carpet. Not reporting suspected corruption carries a three year jail term.

Another positive is giving the CIC power to examine entities or individuals in receipt of Commonwealth funds who are suspected of engaging in criminally corrupt conduct.

The drafting of the CIC legislation will be aided by three independent experts. Let’s hope they can convince the government that when it comes to corruption, a one-size-fits-all approach works best. If you’ve got nothing to hide you’ve got nothing to fear.