On Thursday 30 January, pedestrians in some suburbs of Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane would have walked straight past activist artists (vandals, some critics might call them) removing advertising from bus shelters and inserting artwork protesting the Morrison government and its handling of Australia’s bushfire crisis.

“Bushfire Brandalism”, the action is being called.

Sydney-based artist Scott Marsh chuckles about the hi-vis vests: “It’s the cloak of invisibility.”

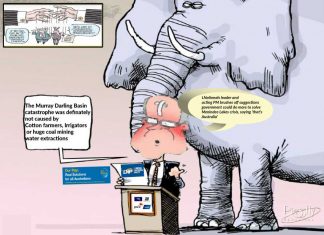

Marsh, known internationally for his political murals, contributed a portrait of Scott Morrison with the words “climate denial” emblazoned across his forehead.

A QR code on each poster links people to a bushfire-related charity of the artist’s choice. It also gives the collective an idea of how and where people are connecting with the campaign.

Unfortunately, many of the works get taken down as fast as they go up. The collective said on Monday they installed 78 posters last week, describing it as “the nation’s largest unsanctioned outdoor art exhibition”. But only a few posters remain.

The practice of “brandalism” – also known as “subvertising” or “anti-advertising” – isn’t new. In 1979, Billboard Utilising Graffitists Against Unhealthy Promotions (colloquially known as “Bugger Up”) was formed in Sydney and spread to other Australian cities, targeting cigarette and alcohol advertising. British artists the KLF have been associated with the practice since the 90s, and in 2015, more than 80 artists took over 600 Parisian bus shelters during the COP21 UN climate change conference.

Forty-one artists are involved in this latest Australian iteration, including Georgia Hill, Tom Gerrard, Sarah McCloskey, Ghostpatrol, Callum Preston and E.L.K, as well as anonymous artists. In one poster, a Caramello Koala has burst and is melting above the words “Save an Aussie icon”. In another, Blinky Bill runs from an encroaching wall of flames.

The collective launched three weeks prior to the posters going up, via a group chat of artists on Instagram. They were dismayed at what they saw as biased bushfire coverage and at the misinformation being shared by some media – particularly the Murdoch-owned press.

“It felt like taking over public space was an appropriate angle to tackle it,” says one organiser who doesn’t want to be named. “There was a lot of discussion about the divided attitudes and experiences of people living in the city versus the regional areas – but we were limited in time and resources, and also those type of ‘adshell’ spaces only really exist in the city centre.”

Many of the artists involved aren’t known for being political in their work. The same can’t be said for Marsh, who has for years responded to policies he takes issue with – starting with Sydney’s lockout laws, when he was an art student living behind the Coke sign in Kings Cross.

“People were losing their jobs and it didn’t make any sense at all – [there was] dodgy stuff when you started looking into it,” he says. “I went to the Keep Sydney Open march, and then had the idea of doing a mural of Casino Mike [Baird, the then-NSW premier].”

Then there was his mural of Alan Jones with a ball gag in his mouth; and one lampooning Israel Folau for the crowdfunding campaign he launched after Rugby Australia stripped him of his contract following homophobic social media posts (Folau is depicted begging next to a Lamborghini).

Marsh’s murals are frequently defaced or painted over, such as his short-lived “Merry Crisis” Scott Morrison mural that lasted three days (he turned it into a merchandise line and raised $131,424.50 for Australian fire brigades) and a saintly George Michael portrait, which got painted over in black ink before locals reclaimed it with pro-marriage equality messages.

Marsh’s depiction of Cardinal George Pell and Tony Abbott – A Happy Ending – was painted over within 24 hours by three men who labelled it “pornography”. On one occasion, Marsh even obliterated his own mural – Kanye Loves Kanye – after he reportedly sold a one-off print of it for $100,000.

“The interactive stuff’s more fun than murals,” Marsh says. “I did a Fraser Anning Easter egg hunt last year.” (Those who found the eggs were encouraged to throw them at the Fraser bunny.) Before last year’s federal election, he made posters of Clive Palmer falling asleep during question time “and invited people to draw dicks on him”.

Sometimes Marsh really goes the extra mile. Not content with the mural of Cardinal Pell in his prison greens that he put up in Sydney 50 metres away from St Mary’s Cathedral, Marsh flew to Rome on his own coin and did the same near the Vatican. When he has to act fast, he has a printed paper version of the mural, pastes it up and finishes the job with paint, but in any case, passersby were surprisingly supportive.

The last of the 78 Bushfire Brandalism posters have now gone up, but for Marsh, tackling the issue of climate change is far from over. He continues to create works relating to the Adani coalmine, not least because of all the family holidays he spent at the Great Barrier Reef.

“It’s really hit home for me,” he says. “I’m frustrated with the lack of action. I got distracted for a while, but you can smell it in the air that now is the time to really push on climate change. If nothing happens now, it’s never going to fucking happen.”

Article originally published in The Guardian