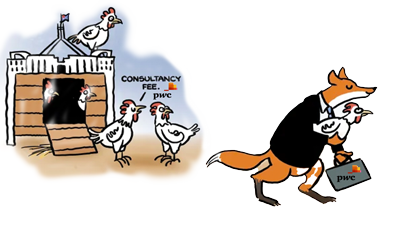

Tax office accused of ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ culture on PwC breach

“We could not provide that information to the assistant treasurer or the treasurer,” Jordan said. “In fact, we could not provide it to Treasury.”

The agencies most involved in responding to professional services giant PwC’s misuse of government information are facing growing concerns about their handling of the breach, including the Australian Taxation Office’s insistence that it could not legally alert government.

In senate budget estimates hearings this week, ATO commissioner Chris Jordan said secrecy provisions prevented his agency from notifying even its portfolio department, Treasury, of evidence that the accounting giant – which held hundreds of millions of dollars in government contracts – appeared to have used confidential information for its own gain.

“We could not provide that information to the assistant treasurer or the treasurer,” Jordan said. “In fact, we could not provide it to Treasury.”

The commissioner said that was the advice from both the ATO’s general counsel and the Australian Government Solicitor. Jordan suggested secrecy laws, which are already under review across government, were sometimes too limiting.

“It is, in a modern day, I feel, very restrictive in sharing information, say, with Treasury,” he said of the provisions. “We had advice that we couldn’t. It would be a breach of the law.”

The Saturday Paper asked the ATO to specify which legislative provisions had prevented any disclosure beyond the Australian Federal Police and the Tax Practitioners Board (TPB).

The ATO cited Division 355 of the Tax Administration Act. Asked to nominate which part of that division, it declined to elaborate. Treasury also refused to be more specific.

But the senate’s economics estimates committee heard that the ATO and the TPB, which subsequently investigated the allegations against PwC and its partner Peter-John Collins, received different advice on exactly the same law.

“It allows a series of exceptions,” TPB chief executive secretary Michael O’Neill said of Division 355 in the act. “Our legal advice said we’re able to, say, engage with the Treasury, because we were able to determine that the Treasury had records which would be relevant to our investigation. So that caused us to seek copies of those records from the Treasury.”

After a two-year investigation, the TPB deregistered Collins for two years in December and rebuked PwC over Collins’s use of information he had received during confidential government briefings between 2013 and 2016 to solicit new clients and advise on how to sidestep the impending laws.

On Monday, PwC acting chief executive Kristin Stubbins issued a statement apologising for the company’s actions.

“Although investigations are still under way, we know enough about what went wrong to acknowledge that this situation was completely unacceptable,” she said.

Stubbins revealed nine partners had been sent on leave, two had been stood down from leadership roles and the wing of the company that consulted to government was being separated from the rest of the business.

“Management refused to provide workers with the improvement notice, initiated a formal challenge of the improvement notice, and held an all-staff meeting where the existence of the improvement notice was denied.”

Evidence to this week’s senate hearings confirmed it was the ATO that first detected in 2016 that confidential information may have leaked.

PwC’s access to that information had been via three sets of consultations involving Peter-John Collins and other unnamed partners, run both by Treasury directly and by the Board of Taxation, also within that portfolio.

Commissioner Jordan insisted the ATO was not legally able, under Division 355, to alert Treasury that its own arrangements had been breached. Division 355 lays out the secrecy provisions guarding “protected information”, defined as information obtained or disclosed under a tax law. It is focused on information relating to an entity’s tax arrangements, not information about whether or not an entity breached a confidentiality agreement.

“Protected information” specifically does not include information obtained under the Tax Agents Services Act. This is the act that governs policing the activities of registered tax agents and the law under which Collins has been deregistered.

Division 355 also contains a range of exceptions to the secrecy provisions, including allowing transmission for the purposes of law enforcement and for deterring multinational tax avoidance and evasion. It allows a tax officer, as part of their duties, to disclose information to any entity for the purpose of administering any tax law.

“There are several exceptions that allow the commissioner to provide protected information,” Victorian barrister and tax law specialist Chris Wallis told The Saturday Paper.

The wording of Division 355 allows disclosure to “any board or member of a board performing a function or exercising a power under a taxation law”.

The Treasury secretary sits alongside the ATO commissioner on the Board of Taxation, which brings together government officials with an advisory panel of selected private sector experts for consultations on tax policy.

Collins was among the members of that panel between early 2016 and early 2020, along with other PwC partners.

But Treasury secretary Steven Kennedy – who stepped into that role in September 2019 – told estimates on Monday that Treasury was only alerted to concerns about Collins when the ATO asked it for copies of confidentiality agreements in 2018 – two years after it first suspected wrongdoing. The ATO made a further request in 2020, but still refused to provide details.

Kennedy said it was the publication on May 2 this year of a 144-page trove of partially redacted internal PwC emails, which the senate estimates committee had obtained from the TPB, that had alerted Treasury to a problem beyond just Collins. The emails involved more than 50 people, with names redacted. These were what prompted Kennedy to refer the breach to the Australian Federal Police to consider criminal charges.

“The senate has done a very good job in exposing these issues,” Kennedy said, calling the revelations “clearly disturbing”.

Some tax and law experts in both the public and private sector are querying the ATO’s assertion that it was hamstrung by the legislative protections.

Labor senator Deborah O’Neill has asked the ATO for more information.

“I think we need to understand the shape of ‘one part of the government can’t talk to another part of the government’,” O’Neill said. “When you assert that the treasurer or the assistant treasurer were not advised – but you were sitting on this information of exploitation of the Australian people, it doesn’t sound like things were working too well.”

Some are also asking whether various agencies did enough, soon enough, and how hard they tried.

“It’s implausible that these two agencies found it impossible to communicate about a serious breach of confidentiality and the blatant profiteering that resulted,” Greens senator Barbara Pocock told The Saturday Paper.

“It suggests to me they weren’t trying very hard to work together to expose and deal with corrupt behaviour. Are we looking at a go-slow, ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ culture at the highest level of these two agencies which worked to protect PwC? In essence, are we looking at a protection racket?”

There is also confusion involving the ATO’s interaction with the AFP. Last week, the AFP confirmed it had received Treasury’s referral. This week, the ATO’s Commissioner Jordan said his agency had “sought to refer the matter” to the AFP five years ago, in 2018 – something AFP commissioner Reece Kershaw did not mention when he appeared before estimates last week.

Jordan said the AFP and ATO had deliberated over the matter for a year and eventually decided there was insufficient information to proceed.

But the AFP had a different take on events. Responding to the ATO evidence, it said in a statement that the ATO had only “requested advice” on whether there was enough information to make a formal referral and had sent “a set of representative sample documents”.

On Wednesday, the TPB’s Michael O’Neill revealed the board had reopened its PwC investigation.

In deregistering Collins on December 22 last year and rebuking PwC, the TPB published detailed explanations for both decisions. The explanation for the PwC ruling makes it clear Collins was not the only PwC partner who had signed confidentiality agreements to access government information.

The TPB revealed on Wednesday that the referral it received from the ATO was solely focused on Collins. Some in the accounting and legal communities are asking why action was taken only against him.

Over the past fortnight, a parade of department and agency heads have confirmed they have demanded assurances from PwC about confidentiality in the wake of the revelations. The TPB’s confirmation of a reopened inquiry followed revelations from Treasury on Monday that PwC is its internal auditor. Last week, the AFP confirmed the company performs the same role there.

The Defence Department said it holds more than $200 million in contracts with PwC. Industry and Health also have contracts of lesser value.

On Tuesday, the financial regulator the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority told the estimates committee it had just completed three contracts with PwC, with a fourth still current, and that it was in discussions with Australia’s banks over whether any information gained from APRA was being used to seek contracts.

And on Wednesday, when explaining how the Reserve Bank was addressing an underpayment of staff, its governor, Philip Lowe, revealed it had hired PwC to advise on governance. It would not be signing further contracts with PwC until things improved.

“If we’re taking advice on integrity and processes and audit from people, we want to know that they meet the standards in their own commercial behaviour that we would expect to meet in our institution,” Lowe said. “If they don’t do that, then we don’t want to work with them.”

Lowe said the RBA expected transparency and accountability and PwC had not met those standards.

“Trust is the cornerstone of their profession, because they’re providing assurance to us,” Lowe said. “And if they can’t be trusted, how can you ask them to provide assurance to us and advice to us?”

Over the past week, more details have also emerged of how the PwC scandal unfolded. It reaches back to late 2013, when Peter-John Collins and unnamed others from PwC were among those Treasury consulted on implementing an international anti-tax-avoidance measure.

That group continued to meet until June 2017, according to a Treasury submission to its minister, Jim Chalmers, written the day before the TPB published its findings against Collins and PwC in December last year, and released under freedom of information law in February.

In addition, some members of that group, including Collins, were also involved in separate confidential consultations on developing tax-avoidance legislation. In the 2015 budget, the then government unveiled its crackdown measures.

Collins joined the Board of Taxation advisory panel early the next year.

The ATO revealed this week that it first became suspicious in January 2016 when new tax laws took effect and “a handful of multinationals” swiftly restructured their business arrangements to sidestep Australia’s new tax-avoidance crackdown.

ATO Second Commissioner Jeremy Hirschhorn said 44 companies had restructured and about a third of those were PwC clients. The ATO prosecuted three companies – Glencore, Carlton & United Breweries and international brewer AB InBev – all of which were PwC clients.

ATO Second Commissioner Jeremy Hirschhorn said 44 companies had restructured and about a third of those were PwC clients. The ATO prosecuted three companies – Glencore, Carlton & United Breweries and international brewer AB InBev – all of which were PwC clients.

Chris Jordan said the ATO issued three alerts about these practices in 2016 and managed to head off the avoidance.

Giving evidence on Tuesday evening, Jordan volunteered that the breach could have cost the taxpayer $180 million in lost revenue. But he said the ATO stopped it.

“We got on top of this early and stopped any tax loss in Australia from this egregious behaviour,” Jordan said. “And this will only harden our resolve to continue the work we do every day to make sure everybody pays their fair share of tax in Australia as the community expects.”

He said when the ATO sought to access PwC’s internal correspondence, the company had tried to claim legal professional privilege to avoid providing it.

“Despite our best efforts, due to the obstacles placed in our path, it took a long time to obtain the information requested,” Jordan said.

The ATO had started to acquire PwC’s internal communications in 2017 and for the two years that followed. In 2019, it took an assistant commissioner and 20 staff offline to focus on the issue.

This week, Michael O’Neill detailed that board’s involvement with the PwC allegations. O’Neill said the ATO had alerted the TPB to its concerns about Collins and PwC at a meeting on April 2, 2020.

A formal ATO referral to investigate PwC’s activities did not arrive until three months later, on July 2, and it did not launch a formal investigation for six months after that, beginning on January 11, 2021, though O’Neill said informal inquiries had begun sooner.

Michael O’Neill said the 144-page collection of internal PwC emails provided to the senate on May 2 this year was a mix of documents collected by the ATO and the TPB. He confirmed it was “not the entirety of all the documents we have in this matter”.

“There may be thousands of documents in this matter,” O’Neill said.

The Greens’ Barbara Pocock asked why PwC had not also been deregistered as a tax practitioner.

TPB chair Peter de Cure, who started in his job on Monday, revealed it had reopened its inquiries but had no immediate plans to sanction PwC further.

Pocock asked de Cure whether he believed PwC had acted “honestly and with integrity” as required by the tax practitioners’ Code of Professional Conduct.

“In relation to what happened in 2015, arguably, no,” de Cure replied. “In relation to what they’re doing today, I would imagine they probably are.”

De Cure rejected Pocock’s assertion that the board had failed to deal adequately with the issue.

“It’s my view that we received a referral from the ATO, and that we dealt with that referral in accordance with the Tax Agents Services Act,” he said.

The senator asked why the TPB had not applied to the Federal Court to impose a fine on PwC, as was possible under the legislation.

“We imposed the sanctions that we thought to be appropriate,” de Cure said. Michael O’Neill then said the fines were only possible “in certain circumstances”.

“Those circumstances don’t apply to the circumstances we found ourselves in with Mr Collins, and PwC,” O’Neill said. “It’s just that the way the legislation is structured.”

Asked why the TPB had opted to ban Collins for two years, not five, de Cure said Collins had expressed remorse, there had been no known repeat of the behaviour and it had occurred five years earlier. He did not expect Collins would ever reapply for registration.

Pocock also asked about conflicts of interest and the fact that two members of the TPB were former partners at PwC who received permanent pensions from the company, linked to profit levels. Both had recused themselves from the investigation and decisions in this case.

“Two members of the TPB would stand to lose money if PwC was suspended, is that correct?” Pocock asked.

“Yes, I understand that to be correct,” de Cure said.

Pocock responded: “Do you understand how this looks just for the average person out there paying their tax? The TPB is fundamentally compromised.”

The government is seeking to strengthen provisions in the TPB Act, with legislation before parliament. Treasurer Jim Chalmers said he was prepared to do more if necessary, suggesting the government and the nation were justifiably “absolutely filthy” about what had happened with PwC.

“We cannot have a repeat of this absolutely appalling episode where people were monetising government secrets, when governments in good faith were trying to consult with corporate Australia,” Chalmers told the ABC’s 7.30.

In parliament, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese called the events “an absolute scandal”.

The TPB has now demanded PwC reveal the names of those involved by June 20. A PwC spokesperson said it would “respond in accordance with the TPB’s request”. The company previously indicated it was seeking to separate the names into groups according to levels of knowledge.

The Greens have vowed to refer the issue to the new National Anti-Corruption Commission when it begins work in July. Pocock queried the time that had elapsed between the first indication of wrongdoing and the sanctions imposed on Collins and PwC on December 22 last year, which only became known publicly when The Australian Financial Review uncovered them in late January.

“The eight-year gap between the ATO having knowledge of active tax avoidance by big multinationals and the slap on the wrist for PwC is a sign of institutional failure,” Pocock told The Saturday Paper. “The Australian community are right to be asking ‘why are these organisations taking so long to address serious corruption?’ ”

Pocock said the average Australian was not given an eight-year grace period if accused of breaking the law.

“It’s a case of one law if you are too big to fail and another for average Australians,” she said.

This article was first published in the print edition of The Saturday Paper on June 3, 2023 as “Tax office accused of ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ culture on PwC breach”.