Clearly absurd’: A fresh account of

“The democratic process is not using public money for party political purposes. That’s not democracy,”

Anne Twomey, professor emerita of constitutional law at the University of Sydney, shot back

Nationals Senator Canavan: “That’s a different issue.”

Scott Morrison’s dodgy grants

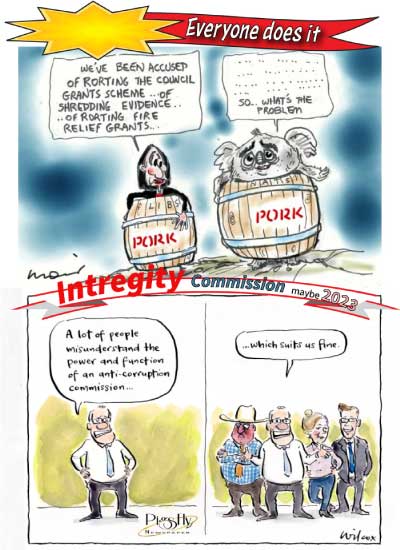

The congestion fund was only one of a number of programs under which the previous government has been found to have used public money for partisan political ends.

There was an utter lack of proper process around government decisions involving the expenditure of billions of dollars on projects, small and large, across a range of portfolio areas.

Transport Minister Catherine King speaks to the press in Hobart, after the federal government pledged an additional $240 million to the Tasmanian government to build a new AFL stadium.

Anne Twomey, professor emerita of constitutional law at the University of Sydney, says it is insane.

“Can you imagine what Barton or Griffith or any of the people who wrote the constitution would say if they were told that the Commonwealth government was going to be making grants spending money on resurfacing a football oval or putting in a set of traffic lights – not that they would have known what a set of traffic lights was – but it’s absurd, clearly absurd.

“It was never the intent that the Commonwealth would do these things.”

Australia’s three-tier system of government was set up so the various levels would take responsibility for different things.

“Is there a Commonwealth head of power for traffic lights?” asks Twomey, rhetorically.

“No. The reality is, traffic lights and sports ovals and all those sorts of things are matters for state and local government.

“And if the Commonwealth is concerned they [state and local governments] won’t be able to properly fund them … then the Commonwealth should fund the states so they can.

“But it’s state and local government that should be dealing with local facilities, deciding priorities. If the Commonwealth is coming in with tiny little pet projects all the time, it’s an insane way to do things.

“The problem is, they want to use money for political purposes rather than in the public interest.”

These projects are funded under the Urban Congestion Fund, a $4.8 billion program that most famously promised $660 million for 47 commuter car parks, heavily concentrated in vulnerable electorates in Melbourne.

A scathing report by the Australian National Audit Office, delivered in June 2021, found the selection process was “not designed to be open or transparent” and “did not include advice on project feasibility, costs, risks or value for money”.

The congestion fund was only one of a number of programs under which the previous government has been found to have used public money for partisan political ends.

The federal parliament’s joint committee of public accounts and audit (JCPAA) is currently inquiring into the administration of Commonwealth grants with a view to strengthening the integrity of the system.

The committee’s terms of reference say it will have “particular regard to” the operation of the Urban Congestion Fund, the Safer Communities Program, the Building Better Regions Fund and the operation of Grants Hubs – all of which were subject to critical reports by the Auditor-General – as well as the Regional Growth Fund and Modern Manufacturing Initiative.

There is a lot to be getting on with, but for obvious reasons the traffic light example was of particular interest to Julian Hill, the Labor chair of the committee.

In questioning David Hallinan, a deputy secretary of the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts, Hill wanted to know what “national urban congestion priorities” were being addressed by the Commonwealth in providing 100 per cent of the funding for lights at a minor intersection on a “one-lane each way” road.

Hallinan could not say.

Hill asked what process led to the decision being made.

The senior bureaucrat was uncertain about the specifics of that particular project. There were so many. Likely, it was one among a “basket” of projects under the congestion fund where “we didn’t get to the point of having BCRs in place”.

BCR stands for “benefit-cost ratio”, meaning the bureaucrats were not afforded the chance to assess the merits of the project against its expense.

Asked about the process of identification of projects for funding, and what consultation there was, Hallinan could only offer this: “The simplest way for me to do this is to say it was a cabinet process. In effect, it was under the banner of cabinet deliberation and decision-making.”

That is to say it was largely unknowable, because cabinet deliberations are secret. Taxpayers will probably never know how or why it was decided to install new traffic lights outside the treasurer’s office.

What is clear, however, from the audit reports and from the evidence to the committee from the likes of Hallinan, is that there was an utter lack of proper process around government decisions involving the expenditure of billions of dollars on projects, small and large, across a range of portfolio areas.

Let’s focus on transport infrastructure. As the Grattan Institute said in a 2022 report entitled “Roundabouts, Overpasses, and Carparks”, “The golden sphere for pork-barrelling is surely transport projects.”

And let’s start small. As Marion Terrill, Grattan’s transport and cities program director, and the lead author of the report, says, there has been a “huge rise” in the number of small projects over the past decade or so.

First point, she says, echoing Twomey, “is that the Commonwealth has got no business being in these small, these hyper-local projects in the first place”.

The federal government, she says, “is supposed to focus on nationally significant infrastructure on the National Land Transport Network; state and local governments are supposed to be responsible for locally important roads and rail”.

And yet, as detailed in the report, since 2009 successive federal governments had funded nearly 800 roundabouts, car parks and overpasses “that are unconnected with the National Network”.

Labor did it, too, although not to nearly the same extent as the Coalition government that followed. Total spending on projects worth less than $10 million was about 10 times higher under Tony Abbott, Malcolm Turnbull and Scott Morrison.

“Voters in marginal seats are the beneficiaries of pork-barrelling in transport infrastructure,” said the report. It noted that, under the Urban Congestion Fund, the average marginal urban seat received $83 million; the average safe Coalition seat received $64 million; for safe Labor seats, it was $34 million. Most of the pork was committed during election campaigns, “when promises are often particularly poorly thought through”.

This lack of consideration of the costs and benefits did not apply only to small infrastructure commitments. Of 22 “megaprojects” worth more than $500 million, committed to by the federal Coalition government between 2016 and 2020, Terrill tells The Saturday Paper “only six had a business case that had been completed and assessed by relevant authority [Infrastructure Australia] before the decision to invest”.

Her report noted a rapidly escalating “arms race” between the major political parties in such unscrutinised election promises. At the 2016 election, Labor and the Coalition promised transport projects valued at $6 billion and $7 billion respectively. In 2019, this had grown sevenfold – the Coalition made promises worth well over $40 billion and Labor almost $50 billion.

Clearly, things were getting out of hand, and steps had to be taken.

Following last year’s election, Labor undertook a review of the role of Infrastructure Australia and subsequently promised to “reinstate Infrastructure Australia’s position as the expert adviser to the Commonwealth on nationally significant infrastructure – to build the nation’s future economic, environmental and social prosperity”.

This week, the relevant minister, Catherine King, announced another review, of the government’s $120 billion Infrastructure Investment Program, a 10-year “pipeline” of promised projects.

The media release announcing the review noted that under the previous government the number of infrastructure projects in the pipeline blew out from nearly 150 to 800, including some 160 projects that had a commitment of $5 million or less.

The release accused the former government of leaving the new one holding “fiscal time bombs” in the form of projects “without adequate funding or resources, projects without real benefits to the public … delays and overruns in important, nation building projects”.

At the JCPAA hearings, three expert witnesses – Twomey; Geoffrey Watson, SC, a director of The Centre for Public Integrity and former counsel assisting the New South Wales Independent Commission Against Corruption; and Kate Griffiths, Terrill’s colleague at Grattan and the institute’s deputy program director, budgets and government – advocated for some straightforward reforms to guard against pork-barrelling or, as Watson prefers to term it, the “misuse of public money” to party-political ends.

Griffiths submitted that federal grants should be awarded through an open, competitive, merit-based process, something that happened in only 13 per cent of cases in 2021. She said that when ministers establish grants programs they should define the selection criteria but should not be involved in choosing grant recipients.

She noted that where ministerial discretion is used to override bureaucratic advice, clear reasons need to be provided, and that there should be more frequent auditing of programs. She added that a multiparty standing parliamentary committee could oversee compliance with the grant rules and interrogate any minister or public official who deviated from the rules.

Twomey said that while it might be legitimate – assuming the government could justify it under a constitutional head of power – to establish a scheme to fund a broad area of spending, “what they shouldn’t be doing is making promises in relation to particular grants to particular communities when they haven’t set out the guidelines or the rules, they haven’t done any merit assessments, et cetera”.

The suggested reforms were not well received, particularly by the Nationals’ committee member, Senator Matt Canavan. He called them “nuts”. He said they were “effectively … advocating for laws to restrict candidates in what they can say and promise to do on getting elected. I want to be very clear about what you’re proposing. You’re not proposing democracy. You’re proposing technocracy. You’re proposing that technocrats in Canberra get all the power to decide what happens in this country.”

Watson and Twomey could not believe what they were hearing and said so in as many words. Twomey took on Canavan directly, arguing that she was actually trying to protect democracy.

“The democratic process is not using public money for party political purposes. That’s not democracy,” she shot back.

The exchange continued as follows.

Canavan: “That’s a different issue.”

Twomey: “Democracy is parliament allocating the expenditure of money for public purposes. That’s democracy.”

Canavan: “Under your proposal would it be illegal for me to say, as a candidate, ‘Elect me and I’m going to get rid of that law that has been passed, so that I can provide $10 million to my constituents’?”

Twomey: “Of course you can do that, because it’s democratic process. Of course you can always say that you’ll propose to change the law. But it might well be that you might find that the people actually appreciate having laws that say that money will be spent fairly across all the electorates rather than in this process.”

Elaborating to The Saturday Paper, Twomey calls pork-barrelling “corrupt”.

She says it might not be corrupt in the sense of individuals personally benefiting financially but is corrupt in the sense that it is engaged in for the purpose of gaining political benefit.

“The system still permits what is essentially corruption,” she says. “And the fact that politicians won’t recognise it as corruption, that [they] get up there and said, ‘Well, people don’t like it, but there’s nothing illegal about it, that’s all okay.’ Well, the reality is … it’s not okay. And they shouldn’t be trying to turn what is essentially corrupt conduct into something that’s completely ordinary and utterly permissible.”

Of course, Twomey says, she and Watson and Griffiths were not proposing “technocracy”.

She goes on to say that the expert witnesses were not arguing that MPs could not promise to advocate for projects, only that those promises should be subject to expert scrutiny and should be scrapped if they don’t stand up, or that, where the bureaucratic advice has been overridden, there should be clear public reasons for that.

This brings us to the Albanese government’s commitments to cleaning up the system.

What struck Twomey about this week’s announcement of an independent review of hundreds of projects in the $120 billion infrastructure investment pipeline was that it excluded promises made at the election – as in, promises made by Anthony Albanese and his candidates.

Marion Terrill is troubled by this, too: “This is obviously in part a political exercise, because it’s carefully excluded announcements that Labor made during the election.”

She can see no rationale for a review that looks for dodgy commitments made by the previous regime but is specifically prevented from bringing the same scrutiny to those promised by the incoming government.

Indeed, as she wrote in her report, election commitments are particularly worthy of examination because “most election promises are not properly scrutinised before the election, and once a party has won office, it often implements promises even if those promises are poor choices, and despite the likelihood that they will cost much more than anticipated”.

Although the previous government had a particularly egregious record when it came to pork-barrelling, “both sides do it”, says Terrill.

“On the weekend, for example, the prime minister announced $240 million for the Hobart AFL stadium. And that’s been nowhere near Infrastructure Australia.”

The first recommendation of the review was that: “Infrastructure Australia’s mandate be defined as ‘the Australian government’s national adviser on national infrastructure investment planning and project prioritisation’. This should include advising the Australian government on its strategies and priorities to invest in transport, water, communications, energy, social and economic infrastructure.”

In its response, the government opted to limit the body’s role to advising on “transport, water, communications and other nation-building infrastructure as appropriate”.

The Hobart stadium is social infrastructure. Therefore, it will not be reviewed, which is unfortunate, as its benefits are questionable. An analysis commissioned by the state government and released in January found the Macquarie Point stadium would generate a loss of more than $300 million over 20 years of operation.

“Of course,” Terrill concedes, “cost-benefit analysis doesn’t capture everything that matters.”

In this case, it would appear that the political benefit of facilitating a Tasmanian AFL team’s entry into the national competition was seen as outweighing the financial risk.

Still, she says, the decision to fund the stadium is ironic coming from Albanese, because, back in 2014, when he was the shadow minister for Infrastructure, he led the efforts by Labor to give greater power to Infrastructure Australia.

“There was a lot of debate, I think 11 hours of debate on the floor of parliament … as Labor tried to get some amendments up and failed.”

What Albanese proposed, she says, was to amend the legislation so as to prohibit the funding of any investment project valued at $100 million or more, unless and until Infrastructure Australia had given the minister a cost-benefit analysis and priority ranking of the project.

He was in opposition then. Apparently things look different from the government benches.

No doubt, the experts say, the new government is bringing greater rigour to the processes whereby government money is spent, compared with its predecessor. But that’s a pretty low bar to clear.

This story was modified on Saturday, May 6, to remove reference to a traffic light project funded in Josh Frydenberg’s electorate. The project was recommended by council in 2019 for funding under the commonwealth program, and was expected to improve safety and traffic flow. At the time the project was announced, Josh Frydenberg’s office was not on the same site. The Saturday Paper apologises unreservedly for the reference.

This article was first published in the print edition of The Saturday Paper on May 6, 2023 as “‘Clearly absurd’: A fresh account of Scott Morrison’s dodgy grants”.