CHOICE?

We obsess over our pollies’ private flaws and peccadilloes and call this politics when actually it’s just gossip.

But when it comes to researching the backgrounds, affiliations and voting records that might deliver politicians, policies and projects we believe in – nah, forget it.

Even if we wanted to take the big-picture view, we’d be ill equipped to do it.

The election, as a device, both promotes the worst candidates and incentivises their worst behaviour.

It fascinates me that, while you and I live snarled in the barbs and infuriations of petty bureaucracy – arbitrary speeding fines, council refusals of backyard follies, strata-bodies’ vengeance feuds, the brute humiliations of the Centrelink crawl and the perpetual requirement to choose medical insurers, super funds and telcos without sufficient information to make that choice intelligent – the big guys breeze on.

Threats of criminal action? Oh, I’m so dreadfully sorry, let me resign forthwith (on my multimillion-dollar pension). Tax? Pah. Tax is what the poor pay and the rich evade. Misleading Parliament? Child’s play between consenting cubby-mates. Why, despite two centuries of democracy, are we still in this angrifying feudal pickle? Because, in a word, elections.

Threats of criminal action? Oh, I’m so dreadfully sorry, let me resign forthwith (on my multimillion-dollar pension). Tax? Pah. Tax is what the poor pay and the rich evade. Misleading Parliament? Child’s play between consenting cubby-mates. Why, despite two centuries of democracy, are we still in this angrifying feudal pickle? Because, in a word, elections.

Elections are democracy’s worst and most dangerous aspect, an own goal exacerbated by the fact that this is counterintuitive. We think the election is the small guy’s secret weapon, our big win against tyranny, our chance to put the dopes and dunderheads out with the garbage and start over. Wrong. Elections are deeply undemocratic. So much so that, absent a miracle, they’ll be democracy’s downfall.

Why? Because of the unhealthy interplay of three core human traits – laziness, status and greed. The election should elicit our most noble, impelling us to learn and discern, to see the big picture, to organise our lives and our cities on lines of principle. Instead it brings out the worst in both politicians and voters.

The laziness is ours. Sure, you could call it time-poverty or burden-of work but, honestly, given that we’re the most leisured society of all time, this has plausibility issues. We can’t choose decent leaders because we don’t have time? Either way, we don’t do the homework we should.

We obsess over our pollies’ private flaws and peccadilloes and call this politics when actually it’s just gossip. But when it comes to researching the backgrounds, affiliations and voting records that might deliver politicians, policies and projects we believe in – nah, forget it. Even if we wanted to take the big-picture view, we’d be ill equipped to do it.

The status yearning is theirs. We are, after all, mostly chimp DNA. Status drives almost everything we primates do. Walk into any room and your first, splitsecond act is to categorise everyone there into ‘‘above’’ or ‘‘below’’ you. True, the criteria are complex and contingent and the people, as you get to know them, often require reallocation. But this hierarchy establishment is immediate and instinctual.

It is also surprisingly consensual. Mostly, the people we agree are “top” are the brutes and boofheads, the rich and the grabby, the relentless competitors, dominators and aggressors. In the electoral arena, this makes our politicians do whatever it takes to get to the “top” and to stay there; our leadership process preselects for those individuals who least possess qualities we actually like or admire; those we actually least want to follow.

Then there’s greed. Greed makes our politicians do things that are ugly and stupid at any time of term but at election time it also implicates us as voters, enabling the shameless pork barrelling by which our politicians woo us. Why did Bronte surf club receive $2 million from the government a week before the Wentworth byelection last spring? Why did the federal government promise a $3.5 billion splurge on the Western Sydney rail link through the marginal seat of Lindsay and a multimillion-dollar overpass through Peter Dutton’s seat of Dickson? Because they assume we can be bought. And cheaply.

Then there’s greed. Greed makes our politicians do things that are ugly and stupid at any time of term but at election time it also implicates us as voters, enabling the shameless pork barrelling by which our politicians woo us. Why did Bronte surf club receive $2 million from the government a week before the Wentworth byelection last spring? Why did the federal government promise a $3.5 billion splurge on the Western Sydney rail link through the marginal seat of Lindsay and a multimillion-dollar overpass through Peter Dutton’s seat of Dickson? Because they assume we can be bought. And cheaply.

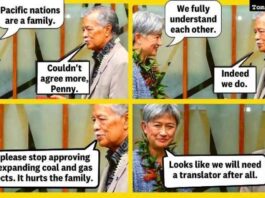

Nowhere has the sulphurous eddy and swirl of money around elections been more expertly parsed than in January’s High Court judgment in Unions NSW v NSW. The NSW government, you may recall, had legislated to cap – in fact to halve – the amount that “third parties” such as GetUp! could spend on communications during election periods. The full seven-judge bench took the unusual step of delivering five discrete but unanimous judgments, all arguing, in subtly different ways, that the government had attempted unconstitutionally to limit our freedom of political speech. Constitutional law in this country often seems a mishmash of wordy expedience but this is a resounding defence of our rights as a people. For the jaded and cynical, it makes an exhilarating 87-page read.

The government argued that candidates and political parties “enjoy special significance” in campaign debate and should therefore be vastly freer to spend election money than any third party. The judges disagreed, arguing that freedom of political speech “extends also to communications from the represented to the representatives and between the represented”.

Refreshing, but the court also recalled existing caps on donations and expenditure were meant “to secure the integrity of the legislature and government in NSW, which was at risk from corrupt and hidden influences of money”. Here, the government’s purpose had been the opposite. Justice Edelman said: “The Parliament of NSW acted with the additional purpose, not merely the effect, of quietening the voices of third-party campaigners relative to political parties and candidates.”

Campaign expenditure implies political donations. And although the judges’ argument pivoted on the impulse to level the playing field, that field is already dramatically tilted the parties’ way. Not only can political parties still spend many many times more on their own campaigns but those millions, harvested from major corporates, bring long sticky strings of post-election influence.

The election, as a device, both promotes the worst candidates and incentivises their worst behaviour.

What would be better? There’s much to recommend banning elections altogether and replacing them with randomly selected citizen juries that encourage collective wisdom and discourage self-interest. Failing that, we’d take strides simply by banning party donations altogether, capping election expenditure to $100,000 (say) for each candidate and funding this from the public purse. As hockey fields go, that’d be a lot closer to the horizontal.

This opinion piece was originally published by Elizabeth Farrelly of the SMH