Google’s £130m tax deal with the UK reveals the need for a radical overhaul of the international tax system, according to Britain’s leading authority on tax and spending.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) said governments should consider going back to the drawing board to develop a tax system that accommodates multinationals which currently escape making corporation tax payments in some countries.

The intervention by the thinktank will put further pressure on George Osborne to explain how the deal with Google was calculated, after HM Revenue & Customs accepted a £130m settlement for tax dating back to 2005.

The transport secretary, Patrick McLoughlin, defended the deal, which experts said amounted to an effective tax rate of 3%, but said he would like to see the US-based search firm pay more tax in the future.

McLoughlin was speaking after MPs demanded that HMRC and Osborne explain the basis for the tax deal.

Google said it would comply with reforms agreed by members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which includes all the major economies. As a consequence, Google would pay tax on profits generated from adverts on its UK site.

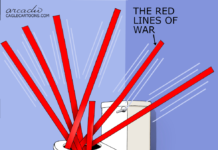

But the IFS said that while the OECD’s new tax rules would prevent some tax avoidance, it represented an extra layer of rules on top of a creaking system dating back to before the second world war.

In a chapter from its Green Budget, published ahead of the chancellor’s spring budget in March, the thinktank said: “It is open to government to pursue a much more radical course of action: to scrap the corporate tax system as we currently know it and write a new one that better serves our objectives.

The world has changed enormously since the current system was designed in the 1920s. Companies’ activities have become more global, digital and intangible.

Google’s tax deal with the UK: key questions answered

A system that forces companies to show their group activities – and therefore how their revenues are made in each country – would shake up a system where profits are allocated as if they were earned by separate companies within the group.

Google charges its UK operations for the costs of software development at its US headquarters. This fee for using the holding company’s intellectual property is then deducted from the UK subsidiary’s profits, alongside the costs of any loans made by Google’s head office.

The IFS said: “We could tax companies based on where their sales occur rather than where their profits are deemed to have arisen. We may not be ready for such radical change yet, but, depending on how well the newly patched up international corporate tax system works over the next few years, we may find it is worth considering whether a new set of tensions would produce a more agreeable outcome.â€

Richard Murphy, a tax expert and critic of the current tax regime, said the OECD rules forced multinationals to produce country-by-country reporting of their sales and profits, which was a step forward. But he called on governments to insist that firms such as Google publish these documents to allow for a public debate over how they should be taxed.

Recognition from the IFS that the international tax system is broken is another step forward when so many governments prefer to tinker. It’s like a Land Rover Defender, which despite one bolt-on after another since it was designed 50 years ago, is now considered past its sell-by date and has seen the last one leave the production line.

Storey by Phillip Inman. Originally published in The Guardian 30th Jan 2016.