Maybe we need to amend the adage about death and taxes being the only two certainties. No offense to Benjamin Franklin (or whoever said it), but taxes don’t look all that certain these days. That’s true at least for a handful of companies whose bankers and lawyers were as busy as ever in January working on deals designed to cushion the tax blow.Â

Here’s a deeper dive into what makes these tax-saving transactions work and why they keep encouraging copycats.

Inversion Guidelines Meant To Scare Aren’t That Scary:

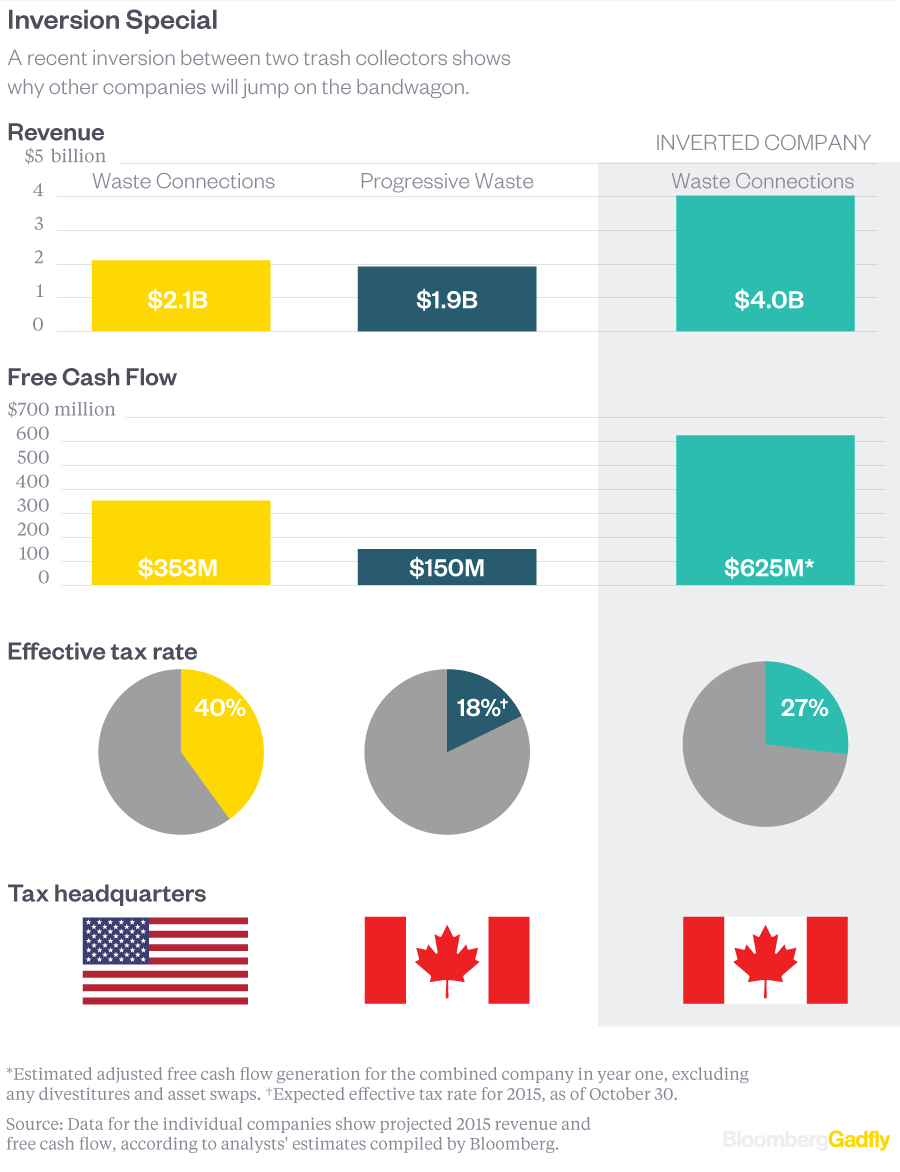

A couple of trash collectors were behind the year’s first big inversion, a move used by U.S. firms to shift their legal address to foreign countries with more friendly tax codes. Waste Connections — based in Texas — agreed to combine with Progressive Waste and take on the latter’s Canadian address.

The deal is structured so that the bigger company, U.S.-based Waste Connections, will end up with 70 percent of the combined business. That puts it in the cross-hairs of strict, new Treasury Department guidelines designed to curb the practice: They take effect when the U.S. company winds up with more than 60 percent.

The Treasury’s proposals don’t prevent inversions, but they do make it harder to structure these deals and take away some of the economic benefits, most notably restricting the ability of inverted companies to tap into overseas cash without paying U.S. taxes.  For Waste Connections — which gets 100 percent of its revenue from the U.S. — the loss of that advantage probably doesn’t matter all that much.

The bigger benefit is the ability to make use of a maneuver called “earnings stripping” — a tactic used by inverted firms to effectively shift profit to lower-tax countries by having the U.S. company pay interest to its new foreign parent on inter-company loans.  Regulators have thus far been unable to shut down the practice and will have a tough time doing so without action by Congress.  The trash collectors’ deal is a reminder that the Treasury guidelines may be stricter, but they’re not tough enough to scare off .

Regulators have thus far been unable to shut down the practice and will have a tough time doing so without action by Congress.  The trash collectors’ deal is a reminder that the Treasury guidelines may be stricter, but they’re not tough enough to scare off .

Tyco’s IRS Victory — A Win For Corporate Inverters Everywhere:

While we’re on the subject of earnings stripping, companies’ ability to keep on using the tactic got support this month through Tyco International’s settlement with the IRS. Tyco did an inversion back in 1997 through its acquisition of Bermuda-based ADT and as such, it’s been engaging in earnings-stripping kinds of practices for some time now. The IRS decided to take issue with that, arguing that the inter-company debt that it used for earnings stripping should actually be treated as equity, which would trigger taxes.

Some $9.5 billion in tax deductions were at issue here, with a potential tax bill of about $3.25 billion, according to estimates by tax expert Robert Willens. But Tyco was pretty careful to set up the relationship as one of debt and it seems that the practice survived the scrutiny. Tyco and its former subsidiaries will pay a much smaller amount of just $475 million to $525 million to the government as part of a tentative settlement. The agreement covers not just the contested time period of 1997 to 2000, but all issues regarding the company’s inter-company loans that are in front of the tax courts. Which means the IRS won’t be bothering Tyco again about this.

This is a big deal for companies that are inverted, or are thinking about it, because it sets a precedent of sorts.

Johnson Controls’ Cash Grab Puts It in Sweet Spot:

Tyco’s settlement may have given Johnson Controls more confidence to pursue an inversion deal with the company. Just days after the settlement was disclosed, Johnson Controls announced it was merging with Tyco and moving its legal address to Ireland. Unlike the trash collectors’ all-stock inversion, this deal included a cash payout for Johnson Controls shareholders, which helped dilute the U.S. company’s ownership stake to below that troublesome 60 percent threshold.

In order to make that work, the cash has to be supplied by the foreign company, the technical acquirer here. Waste Connections probably didn’t have that option in its deal because Progressive Waste is smaller and has a decent-sized debt burden already. Plus as discussed, it wasn’t really all that important for the company to avoid the Treasury’s new guidelines. In Johnson Controls’ case, Tyco is the one ponying up the cash. This is the same tactic that Pfizer employed in its deal with Allergan — which raises the question of whether the Treasury Department will try to do anything to shut down this work-around. For now, though, Johnson Controls looks free to to enjoy the full benefits of its inversion, including accessing overseas cash.

Lockheed Finds Just the Right Partner:

It wasn’t an inversion, but Lockheed Martin’s divestiture of its information-technology business was tax-efficient in another way. The deal was structured as a Reverse Morris Trust, a move used by larger companies to in effect sell unwanted assets to a smaller partner without triggering the tax bill that would come with a traditional sale. This is how it will work: Lockheed will split off its IT division and then merge that business with Leidos Holdings. There are different ownership thresholds at play here to make this work. Instead of 60 percent, the key number is 50 percent. Lockheed has to own at least slightly more than half of this newly formed combination in order for the deal to be tax-free. Otherwise, the whole thing is considered part of a plan (a naughty word in tax land) and taxes take effect.

Leidos was just small enough to make the cut. Its shareholders will wind up with 49.5 percent of the new company. Perhaps that answers some of the questions as to why it was the winning bidder for a business that drew interest from quite a few. The math just adds up.

–Rani Molla contributed graphics to this story.

This column does reflect the opinion of Pigsfly

Newspaper.The transaction is structured as a reverse merger, whereby Waste Connections will combine with a newly formed subsidiary of Progressive Waste, which then plans to consolidate the shares.

This is a typical structure for inversions, such that the surviving corporate parent is a foreign one even if it’s really the U.S. company that’s in charge.

This is why Allergan is technically the acquirer in its $160 billion inversion deal with Pfizer.

The U.S. is somewhat unique in the fact that it taxes its companies on not only the profits they make in America, but also on whatever money they earn abroad and bring back home.Rather than pay the tax bill, many firms have elected to keep cash overseas.

Inversions were a way to make use of that stockpile. For a company like Pfizer, which has billions hoarded overseas, that’s an important benefit — important enough that the drugmaker made sure to structure its deal with Allergan so as to avoid the new Treasury guidelines trying to eliminate that advantage.

Originally published BloombergGadfly by Brooke Sutherland 29th Jan, 2016