13 ways to fill Budget Black Hole

![]()

Treasurer Chalmers has a $70 billion a year budget hole: we’ve found 13 ways to fill it

Kate Griffiths, Grattan Institute; Danielle Wood, Grattan Institute, and Iris Chan, Grattan Institute

No one likes spending cuts and tax hikes, but on our estimate the government will soon need more of them if they are going to make a dent in looming A$70 billion a year budget deficits.

A new Grattan Institute report, Back in Black? A menu of measures to repair the budget argues the present combination of low unemployment and high inflation makes this a good time to start to put things in order.

The sooner we do, the sooner we will be well-placed to respond to future economic shocks and avoid pushing costs onto future generations.

We were right to spend big when COVID hit

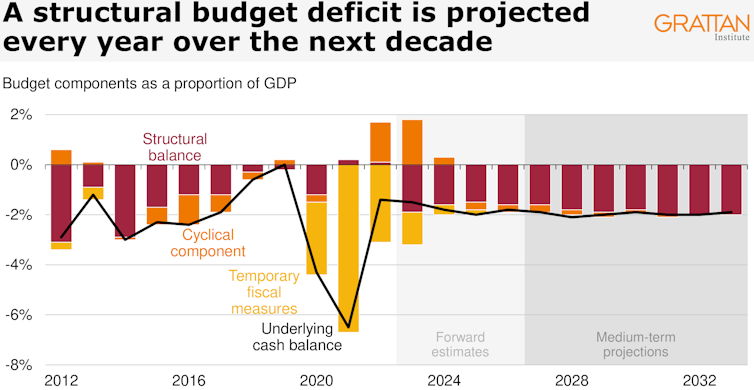

The massive government support unleashed during the 2020 and 2021 lockdowns was essential for supporting households and businesses and helped keep unemployment low and Australia’s 2020 recession mild.

It left us with government debt that, at 23% of GDP, set to climb to almost 32% by the end of the decade, is high by historical standards, but low by international standards.

Our real problem is a structural one of spending growing faster than revenues.

And it was building long before COVID.

Demands on government are set to grow

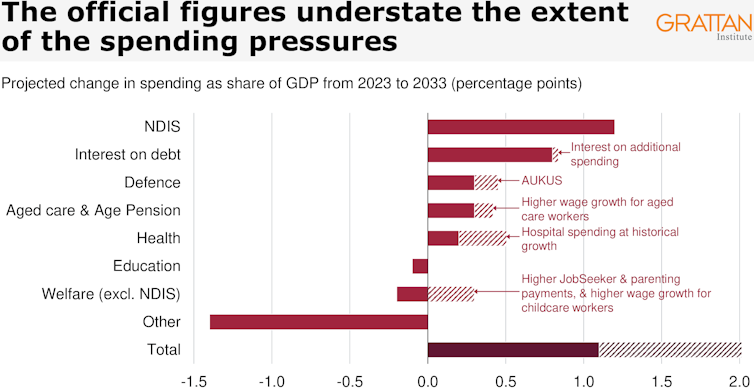

Costs are inexorably growing for three reasons.

The first is that our expectations are growing as we age and become more wealthy, pushing up spending on healthcare, disability care and aged care.

The second is that many of these services happen to be the hardest to mechanise, meaning there is little we can do to stop them costing more over time.

The third reason is geopolitical and climate developments. The huge AUKUS deal is just the latest manifestation of pressure to ramp up defence spending. Increases in the frequency and severity of natural disasters mean we have no choice but to spend more on emergencies than before.

Combined with higher interest rates that are pushing up the cost of servicing debt, these three forces are set to leave a persistent gap between government revenue and spending of about 2% of GDP according to Treasury calculations. That’s $50 billion per year in today’s dollars, each and every year.

Source: Treasury, October 2022 Budget, Chart 3.20

But even that grim forecast looks optimistic.

Grattan Institute estimates suggest the true structural gap exceeds $70 billion per year when extra, largely unavoidable, spending is taken into account – including on AUKUS, overdue wage rises for care workers, more realistic growth in hospital spending, and long-overdue increases in unemployment benefits.

See Figure 1.2 in Grattan report for a full explanation and sources.

And that’s just the next decade. In the longer term, the budget will come under extra pressure from slower productivity growth, Australia’s ageing population, and climate change.

Higher economic growth and productivity growth would reduce the enormity of the challenge, and Grattan Institute has put forward ideas about how to support this before.

But hoping we will be able to grow our way out of chronic budget deficits is not a prudent approach. While we should try to boost growth, by itself it is unlikely to get the nation’s finances onto a sustainable trajectory.

13 multibillion dollar ideas

The size of the problem, and the political difficulty of budget repair, mean both spending and revenue measures need to be on the table.

Spending cuts have been the focus of budget repair efforts for most of the past decade, so a lot of the low-hanging fruit has already been picked. But there are still savings to be had.

The biggest would come from greater discipline in decisions about what to spend on infrastructure and defence. Better decisions upfront based on economic – rather than political – considerations could save several billion each year.

Buying smaller, more regularly and “off the shelf” would reduce the risks and costs of mega-projects that have a history of massive cost overruns.

Our report identifies a further $15 billion a year of savings measures, including undoing Western Australia’s special GST funding deal, counting more of the family home in the age pension asset test, and improving hospital efficiency and purchasing in health.

But even with substantial spending cuts, tackling Australia’s budget challenge without compromising core services will require more revenue.

The biggest opportunity comes from plugging “leakages” in the income tax system. Tax breaks and minimisation opportunities are growing. Reining in superannuation tax concessions, reducing the capital gains tax discount, limiting negative gearing, and setting a minimum tax on trust distributions could collectively raise more than $20 billion a year.

Reworking the legislated Stage 3 tax cuts so they are less generous at the top end would save another $8 billion per year.

Lifting the age at which people could get access to their super from 60 to 65 and freezing compulsory super contributions at their present level (10.5% of salary) would save at least another $8 billion.

Other options include lifting the rate of goods and services tax (with a compensation package, and the Commonwealth and states sharing the net revenue), winding back fuel tax credits and beefing up the petroleum resource rent tax.

Ordering the whole menu at once would be a recipe for indigestion. But if Treasurer Jim Chalmers chooses just a few items on the menu, we will be well on the way to tackling Australia’s budget problem.

Kate Griffiths, Deputy Program Director, Grattan Institute; Danielle Wood, Chief executive officer, Grattan Institute, and Iris Chan, Fellow, Grattan Institute

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Treasurer chooses words carefully as report recommends tax reform to fix budget hole

Facing a possible $70 billion deficit by the end of the decade, Jim Chalmers played coy about what economic moves the government may make.

John Buckley @johnbuckley_

John Buckley penned this article as a reporter at Crikey. He previously covered national affairs and politics at VICE, and his reporting has appeared in The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age, and The Washington Post, among other publications.