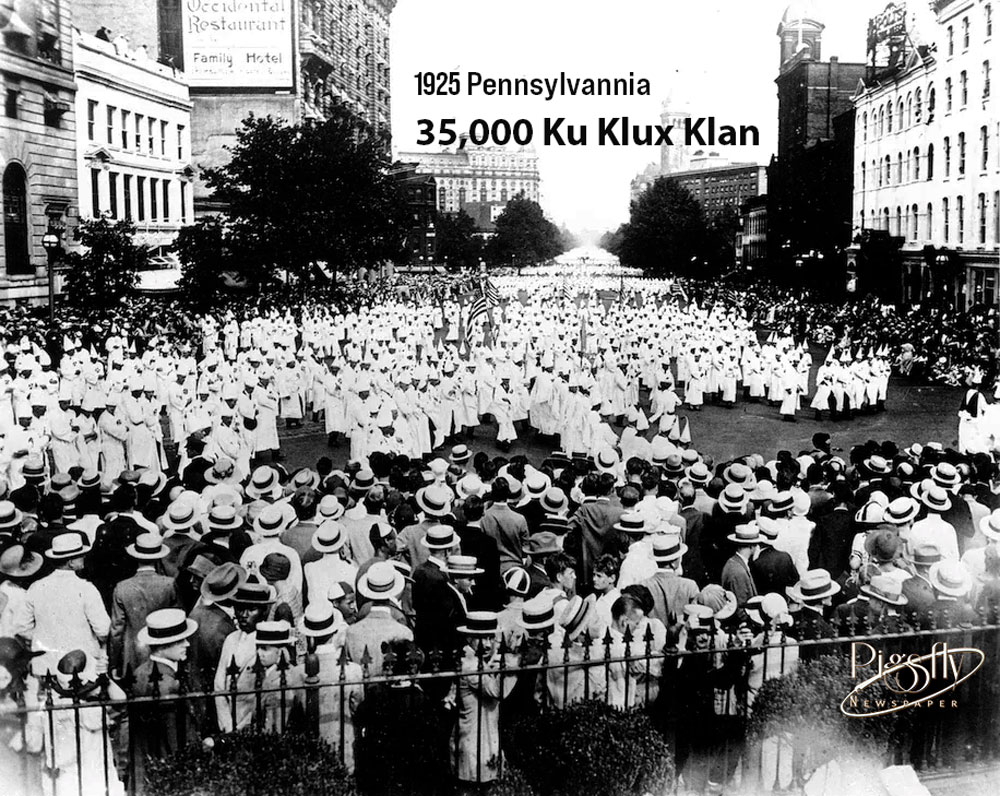

35,000 members of the Ku Klux Klan marched

It’s an astonishment — still — that the visible face of the “Invisible Empire” at the height of its power was Main Street. And nowhere was the Klan more popular than Indiana, where 1 in 3 White males took an oath to “forever uphold white supremacy.”

The man leading the Klan’s takeover in the Midwest was a gifted charlatan named D.C. Stephenson. He controlled the Indiana governor, the state legislature and had his eyes on a vacant Senate seat. Few doubted his boast that, in Indiana, “I am the law.”

Those who puzzle today over the rise of white nationalism, the spike in hate crimes against Jews, a fear of dark-skinned immigrants “replacing” a shrinking White majority or the intolerance of new lifestyles can look to the 1920s to see a not-so-distant mirror.

The Klan boasted nearly 6 million members nationwide in the ’20s — a somewhat inflated number, but still vastly more than the original KKK born in violence just after the Civil War. A Klan mayor ruled Anaheim, Calif. Oregon elected a Klan-backed governor in 1922, and civic leaders in Portland posed with hooded Knights of the Order. A Klan chapter was chartered on board the USS Tennessee, a battleship anchored off Bremerton, Wash. (The population from the 1920 census recorded Pennsylvania 8,720,017; Illinois 6,485,280; Ohio 5,759,394; Texas 4,663,228)

Enormous Klan rallies, promoted from Protestant pulpits, featured oompah bands and barbershop quartets. The wives of Klansmen belonged to a women’s auxiliary. Their children were issued junior-sized robes and masks, and they marched in parades under the banner of the Ku Klux Kiddies. At the core of it all was unabashed white Christian nationalism.

The original Klan, started by ex-Confederates chafing in a country where millions of people who had been held as property were now citizens, directed its terror at Black Americans.

The reborn Klan expanded its range of hatred to the changing face of America: immigrants, Jews and Catholics. They also tried to repress the social liberation of women — in speakeasies thick with jazz, in film and in other cultural expressions.

Substitute today’s opposition to drag shows for the Klan’s campaign against changing morals and uncorseted flappers and you have another haunt of history.

Those who want to turn back the demographic clock in the 2020s, who long for an America belonging to one race and one religion, will find a blueprint in the 1920s Klan.

Just as so many of those who stormed the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, were found to be everyday folks with good jobs, Klan membership in the 1920s was a cross section of White America. But make no mistake, those people belonged to a masked, highly secretive hate group and knew full well what they’d signed up for. They were not ignorant of their Klan oath.

For a time, it was common to see flaming crosses all over the Midwest — after baseball games, at Independence Day parades and Christmas week sleigh rides. When the grandchildren of leading White citizens later discovered hoods in the attic, or membership lists that included their kin, they would tell themselves that it was a Mayberry Klan, social in nature, nonviolent or that its members were dupes in a fraternal order with silly rituals.

None of it was true. The Klan in the Midwest boycotted Jewish-owned shops. They passed laws to prevent Blacks from moving into White neighborhoods or going to public schools of their choice or marrying people from another race. In Indiana, they voted overwhelmingly for the Klan slate in state and local elections. On occasion, they clubbed and terrified their enemies, or ran them out of town.

At a Fourth of July rally outside Kokomo, Ind., in 1923, the Klan attracted up to 200,000 people — the largest gathering in the history of the group, according to the Klan newspaper. A few years later, a crowd would gather in Marion, Ind., to pose with the corpses of two Black men who had been lynched by a mob. No one was ever brought to justice for the vigilante killing.

The hooded order of the 1920s moved quickly from basements in the Midwest to the halls of Congress. At its peak, the Klan claimed four U.S. senators as sworn members, and dozens under its control in the House of Representatives. By 1925, the ultimate political design seemed to be within reach: a Klan from sea to sea, north to south, anchored in the White House.

Resistance to the Klan is part of our history, too. In Indiana, some Hoosiers — two rabbis, an African American publisher born enslaved, a fearless Irish Catholic lawyer and single woman without money or power — were heroic in the face of threats to their lives.

Stephenson, Indiana’s grand dragon, was a violent sex predator who’d gotten away with rape and assault for years because he felt invincible. What finally brought him down was one of his victims, Madge Oberholtzer, whose words in a court of law marked the beginning of the end of the Klan at its most powerful. Membership cratered after similar scandals showed the vile and criminal character of Klan leaders.

The perceived grievances and antidemocratic instincts that gave rise to a massive Klan 100 years ago — our worst angels — have surfaced once again. The lesson of the past is to see the true face of it all, unmasked, and not be afraid to confront it.

Article first appeared in The Washington Post

Trump’s indictment, the Wisconsin Supreme Court election, Tennessee’s expulsion of Democratic lawmakers and abortion pill decisions are a reminder of how unsettled the country is and what’s at stake in 2024

No one disputes what the two expelled Democratic legislators — and a third Democratic lawmaker, who came one vote shy of expulsion — did in Tennessee by engaging on the House floor in a wider protest at the state Capitol broke the decorum of the state House.

But against the backdrop of what had happened at a Christian school nearby, another horrific episode of gun violence that has become endemic in the United States, Republican legislators only looked inward and found a way to add fuel to the flames of division and disagreement.

Preston’s case is one of several violent episodes stemming from last summer’s rally, including the death of Heather D. Heyer, a 32-year-old paralegal who allegedly was run over by James A. Fields Jr., a self-professed neo-Nazi. Fields has been charged with first-degree murder and is scheduled for trial in November.

Four other men also were arrested for taking part in the brutal beating of DeAndre Harris, a 20-year-old African American counterprotester, inside a parking garage near police headquarters. Like Preston’s gunfire and the car crash that killed Heyer, the Harris beating was caught on video.

Two of Harris’s attackers were convicted of malicious wounding last week. A jury recommended 10 years in prison for Jacob Scott Goodwin, 23, a white nationalist from Arkansas, and six for Alex Michael Ramos, 34, a former militiaman tied to a group called the Georgia Security Force Three Percent. Moore is scheduled to set each man’s sentence in August.

In interviews with reporters, Preston identified himself as the imperial wizard of the Confederate White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, based in northern Maryland, and said he attended the rally to protest the removal of a statute of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee from a Charlottesville park. Public records indicate that Preston lives in Bel Air, about 20 miles north of Baltimore.

“We didn’t go as the Klan. We didn’t go there to create havoc and a fight,” he told a news station in Indiana. “We went there to protect a monument.”

He told the Baltimore Sun, “We came there to try to keep the peace.”

But shortly after the rally, the American Civil Liberties Union of Virginia obtained video of Preston shooting his weapon at Long and passed it to authorities. About two weeks later, he was arrested.