Lachlan Murdoch could well have won his Crikey lawsuit, so why did he drop it?

Late last week, Lachlan Murdoch dropped his defamation claim against key figures behind online publication Crikey.

Murdoch had a strong case. So why would he choose to drop it?

The facts of the case

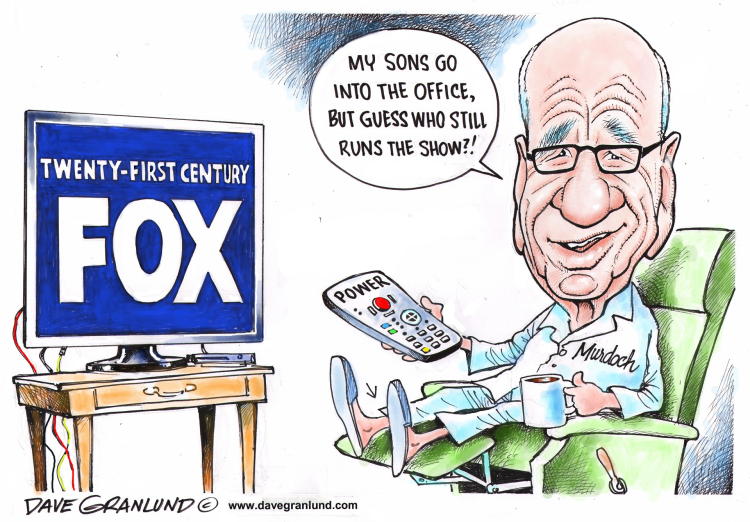

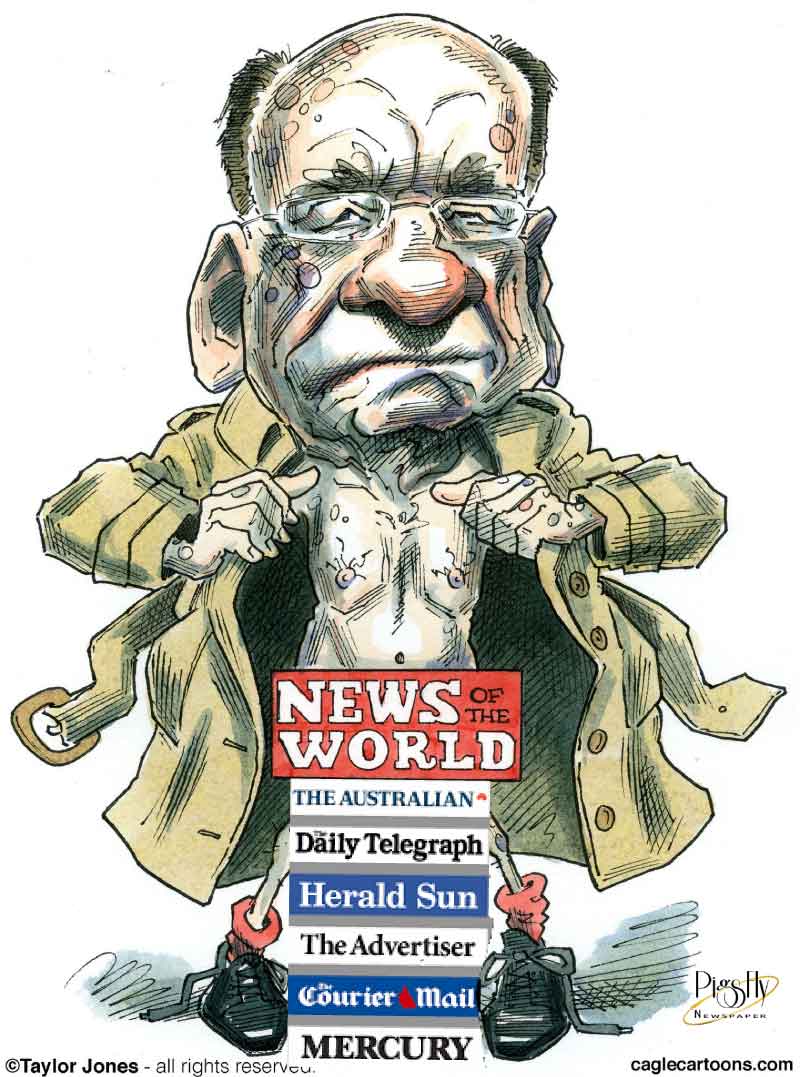

For those under a rock: Lachlan Murdoch is the son of Rupert. He is an Aussie-American-Brit leading News Corp and Fox Corporation. His empire includes Fox News in the US and Sky News in Australia.

Mr Murdoch was suing over a June 2022 article on the subject of the January 6 insurrection at the US Capitol.

The piece called Donald Trump a “traitor”, and Lachlan Murdoch Trump’s “unindicted co-conspirator” – a reference to Richard Nixon’s treatment by a grand jury with respect to the Watergate scandal.

The underlying allegation was that Fox News had supported Trump’s “Big Lie” that the 2020 US presidential election was stolen, which led to the insurrection; and that Lachlan Murdoch was responsible for Fox’s role in spreading the Big Lie.

After the article was published, Mr Murdoch sent the publishers of Crikey a “concerns notice”, essentially threatening to sue them.

In response, the publishers almost dared Lachlan Murdoch to sue. They even took out an ad in The New York Times.

According to Mr Murdoch, those behind Crikey used his defamation threat as part of a marketing campaign to drive subscriptions.

Challenging a billionaire to a defamation fight may not have been the smartest move. In September 2022, Mr Murdoch commenced proceedings in the Federal Court of Australia. He sued the company publisher of Crikey, its editor, and the article’s author. Later, he also sued the chair and chief executive of that company.

Crikey’s defences may have failed

The Crikey respondents were defending the case on a number of bases. Each of these defences relies on legal principles that excuse the publication of content that is defamatory for the sake of other important interests.

Perhaps their strongest defence was a new one – a statutory defence of “publication of matter in the public interest”. The defence became law in 2021. It means a defamatory publication is defensible if two conditions are met.

First, the publication must concern an “issue of public interest”, which the Crikey article clearly did. Second, the publishers must have “reasonably believed” that the publication of the matter (the article) was in the public interest.

The case may have turned on this second element of the new defence. What did the publishers believe? Was their belief about the public interest, or driving subscriptions for Crikey? There was a decent risk a court would have gone with the second option, and the defence would have failed.

If the defences had failed, Mr Murdoch would have won. So why would he choose to discontinue his case?

The Dominion case

Just days ago, Mr Murdoch’s Fox settled what would have been one of the biggest defamation cases of all time.

Dominion Voting Systems sued Fox in the US, and sought a whopping $US1.6 billion ($2.39 billion) damages.

It is extremely difficult to succeed in a defamation case against a media company under US law. But if ever there was a case where it could happen, this was it.

Through pre-trial procedures, Dominion had uncovered a treasure trove of evidence from people at Fox – including from the likes of Tucker Carlson and Rupert Murdoch.

There was plenty of ammunition for Dominion to argue Fox was deliberately spreading lies about Dominion, which would have been required for Dominion to succeed.

Just before the trial was about to start, Dominion agreed to put an end to the case in exchange for a $US787.5 million payment ($1.178 billion) from Fox.

This was a steep price for Fox to pay, but a loss would have cost substantially more in damages. And it would have cost more than money.

If the case had proceeded to trial, it would have caused tremendous damage to the Fox brand and that of its talking heads, further alienating the audience on which they depend.

The evidence already uncovered was ugly, but it was about to get even uglier.

A sound decision

If Lachlan Murdoch continued the Crikey case, then all of the dirty laundry that was to be aired in the Dominion case could have been aired in Australia.

According to the principle of open justice, that evidence would have been heard in an open court, with the global media watching.

Fox’s key benefit of the Dominion settlement – making the story go away, and not having to uncover further evidence – would have been destroyed. It would have been a massive own goal.

It’s likely Lachlan Murdoch would have been cross-examined.

Other reasons to end the case

Say the case continued, and Lachlan Murdoch won. This would mean the Crikey respondents failed in their reliance on the statutory defence of “publication of matter in the public interest”.

The resulting judgment could set a precedent undermining the value of the new defence.

It is in Lachlan Murdoch’s ultimate interest that the defence remains strong; it will protect News Corp rags from publishing defamatory articles, which they are prone to do. Laying down his weapons now avoids that scenario.

And there is the reason Lachlan Murdoch has given for ending his case – he does not want to give Crikey any more ammunition for a marketing campaign to attract subscribers.

Mr Murdoch insists he was confident that he would have won his case. He may have won defamation damages, but he could have lost far more.

Mr Murdoch may end up having to pay the legal costs of the Crikey respondents. But this case was never really about money. As the judge said a few weeks ago, it was more about “ego and hubris”. Many defamation cases are.

Michael Douglas, senior lecturer in law, The University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

With Lachlan Murdoch ceasing his litigation against Crikey, Bernard Keane reflects on what motivated Crikey in a battle against a media behemoth, and why it continues to matter.

If you think that Fox News spreading lies about the 2020 presidential election, and the direct relationship between that and the January 6 2021 insurrection, are now merely matters of historical interest, take a look at the current polling for Donald Trump against his strongest Republican challenger, Ron DeSantis.

Trump will almost certainly be his party’s candidate to face off against Joe Biden in 2024. And he is promising more aggression, more authoritarianism and more retribution if he wins. That’s bad news for US democracy, and for countries like Australia that rely on the US for their security (and we’ve stupidly doubled down on that to the tune of hundreds of billions of dollars under the Albanese government).

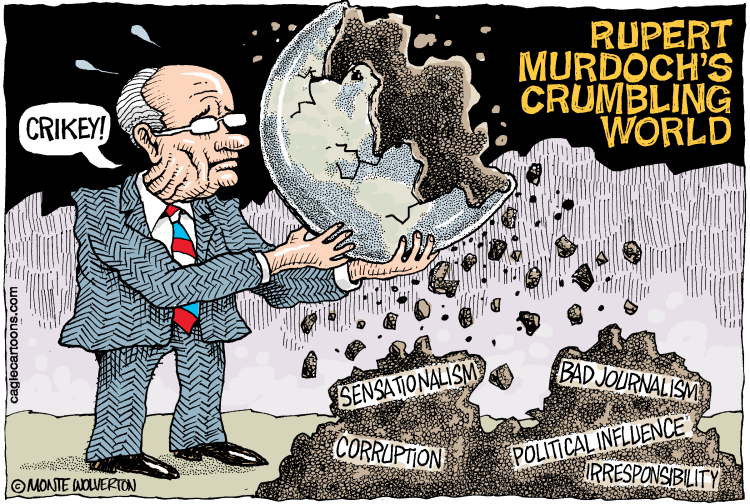

Fox News will lie again to help Trump back into power, if it can. Not because (or merely because) Trump aligns with the reactionary values of the network, or of the Murdochs, but because it’s good business. The Murdochs long ago discovered that vast profits could be made from a media outlet that functioned as a political party, selling grievance, victimhood and conspiracy theories of demonic “liberal elites” to older white Americans. Trump is the avatar of the Murdoch business model, whatever personal feelings Rupert may have about him.

The costs of that model — polarisation, extremism, political violence and incompetence — are borne by everyone else. Or at least they were until COVID began killing Fox viewers who believed the anti-vaccination and “it’s all a hoax” tripe peddled by the network.

When I pointed out the role played by Fox News — and thus Rupert Murdoch and his family — in the January 6 insurrection, much of the information about the inner workings of Fox News had yet to emerge from the Dominion case. But it was hardly an act of prescience on my part. It was already a common topic of commentary in the US media. One of the United States’ best media commentators, Brian Stelter, had explained in detail the extent to which people within Fox News had decided that the prospect of losing extremist viewers due to the fact that the network was endorsing a reality-based analysis of the 2020 presidential election was too much.

My only original thought was to reflect the fact that we’d just had the 50th anniversary of Watergate in early June, and note how far Trump exceeded the previous historical exemplar of presidential misconduct, Richard Nixon — and how much the US media landscape had changed since the 1970s. Thus the now slightly even more famous phrase “unindicted co-conspirator”.

For a statement as unexceptionable as that, it came as a surprise when a personal lawyer for a member of the Murdoch family not even named in the piece contacted us in order to threaten litigation. Surprising for a media mogul with his own array of platforms and, he says, a deep commitment to free speech and a free press. And surprising for the lack of legal nous. Every lawyer that our then-editor-in-chief Peter Fray spoke to — and he spoke to a lot of them — concluded that Lachlan didn’t have a chance. After a good faith effort to resolve the matter, during which we took the article down, a lack of progress meant we had to fight.

Right from the outset, Fray was determined to do so, and he never resiled. And he was strongly backed by our CEO Will Hayward, our chairman Eric Beecher, and our colleagues at Private Media, despite the stakes involved. All media companies will at times respond to legal threats by copping it sweet. Even though you know you’re right, you decide it’s just not worth it. You roll over, issue an apology or take an article down, pay some money and move on.

But Fray was very clear that we were not going to roll over. This was Crikey’s core business of holding the powerful to account. That’s what Crikey, through all its iterations since Stephen Mayne established a gossipy shitsheet over 20 years ago, has always tried to do.

So we committed to back our journalism, to back the importance of a free press — and to hopefully take advantage of a new addition to our rotten defamation laws, the public interest defence. And to their everlasting credit, at no stage did Fray, Hayward or Beecher deviate from that. It’s a matter of enormous pride to me that I work for a company, and with colleagues, prepared to stand up for what’s important, even when it costs a very large amount of money and resources for a small company.

Perhaps Murdoch assumed we’d roll over. Instead we worked out a battle plan, called on our subscribers and took our case public. Facing an existential threat, we called for help from people who share our mission of holding the powerful to account. They responded in droves.

Murdoch’s legal team, and News Corp, later tried to portray this as part of a deliberate campaign all along to use Murdoch as a fundraising tool — as if the original article had been written to order as part of Operation Use Lachlan To Boost Subscriptions.

Well, memo for Mr Murdoch — and for every other reader. I’ve never written to direction at Crikey, and have never been asked to. I write what the evidence leads me to conclude, rightly or wrongly, even if it offends readers because I’m not supporting their favourite political party or cause. I intend to keep doing that. I’m too old and foul-tempered to do anything else.

But it’s disappointing that we won’t have the opportunity to pursue Murdoch in the witness box, nor to establish what would hopefully be a positive precedent of a successful use of the public interest defence. That remains untested.

Going into court, even alongside more experienced hands like Peter and Eric, would have been an unpleasant experience, and an expensive one for the company. I’m certainly relieved that I no longer face that. But I’ve been an armchair supporter of free speech and a free press for many years, so I couldn’t complain about finally being called into the fight.

And in the end, my stress would have been trivial compared to the price being paid by so many others — not just journalists — who have sought or continue to seek to hold to account the powerful. Annika Smethurst. Sam Clark and Dan Oakes at the ABC. Nick McKenzie at Nine. Brittany Higgins. Richard Boyle. David McBride. Bernard Collaery and Witness K. Most of all, Julian Assange. Australians who have paid, or continue to pay, a real and sometimes massive price for doing what’s right.

I’m also lucky we’ve had enormous support from readers, and from many in the wider community who gave, sometimes very generously, to our support fund. It made a huge difference not just financially but knowing that so many people were prepared to stand behind us.

To those who did so — thank you. You’ll never know just how much strength it gave us to know you were backing us.

Were you glad to see Lachlan Murdoch call off his case against Crikey? Let us know by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

Bernard Keane — Politics Editor @BernardKeane

Bernard Keane is Crikey’s political editor. Before that he was Crikey’s Canberra press gallery correspondent, covering politics, national security and economics.