We Build The Future

Mining coup in Queensland removes public objection rights

Lock the Gate Alliance/Flickr, CC BY

Chris McGrath, The University of Queensland

The Queensland government has recently removed long-standing public rights to object to mines.

In shades of the Bjelke-Petersen era, Queensland mines minister Andrew Cripps made fundamental changes one minute before the bill was passed by the Parliament at 11:57pm, just shy of midnight.

The changes broke promises that Cripps had made repeatedly from the outset of public consultation on the bill and during debate in Parliament that public rights to object to large mines would be retained.

The changes sparked blistering criticism. Queensland Country Life described them a “sell out” while broadcaster Alan Jones called the changes “corrupt” and “unbelievable” amidst other colourful language.

What objection rights have been lost?

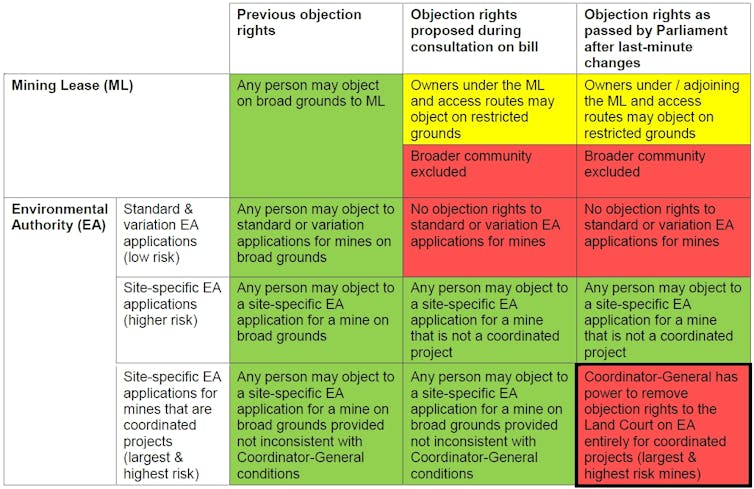

The changes affect public notification and objection rights for the two major approvals needed by a mine at a state level in Queensland: a mining lease and an environmental authority.

Large mines and other developments in Queensland can be declared a “coordinated project” by a powerful public servant, the Coordinator-General, whose role is to facilitate the economic development of the State.

For many decades in Queensland any person could object against the grant of a mining lease and have their objection heard by an independent court, which then provided a recommendation to the government on the application. The grounds permitted for an objection were very wide and included impacts on the environment and the public interest.

This objection right was an important part of the campaign to stop mining on Fraser Island in the 1970s and led to a famous win regarding the concept of the public interest.

Prior to the changes, any person could also object to an environmental authority and have their objection heard by the Land Court. Again, the grounds permitted for an objection were very wide and included things like the harm a mine would cause to groundwater and biodiversity as well as noise and dust impacts.

In the past, objection rights were only constrained by not allowing challenges to the conditions recommended by the Coordinator-General. However, neighbouring landholders and others could argue the mine should be refused due to its impacts on groundwater or other matters.

In practice, few objections proceeded to a full hearing in the Land Court and those that did each year could normally be counted on two hands. For most landholders and other members of the community, the objection process is intimidating and too costly. Objections by landholders and others are invariably a David vs Goliath affair with massive mining companies out-resourcing locals.

However, in one recent case involving the massive Alpha Coal Mine proposed by Gina Rinehart’s company and GVK, local graziers and other objectors succeeded in having the Land Court make a primary recommendation that the mine be rejected due to uncertainty about groundwater impacts. This was in spite of the Coordinator-General’s recommendation to approve the mine and federal government approval of it.

Broken promises

Broken promises

In early 2014 the Queensland government proposed to confine the objections and notifications process for a mining lease to people owning land within the proposed lease. However, the government said it proposed to continue to allow objections to an environmental authority for large, high risk mines to be made by neighbours and others.

In June the government introduced these proposed changes to Parliament in the Mineral and Energy Resources (Common Provisions) Bill 2014.

The proposed changes went out for public consultation and hearings by a Parliamentary Committee. The minerals industry supported the changes but the vast majority of public submissions opposed them.

The Bill was debated and passed by Parliament on Tuesday September 9.

At 11:56pm, one minute before the Bill was passed, the Mines Minister moved a series of amendments. These included inserting a new section 47D into the State Development and Public Works Organisation Act 1971 controlled by the Coordinator-General.

The last-minute changes mean that the Coordinator-General can prevent any objections to the environmental authority for a coordinated project from being heard by the Land Court. When combined with the severe restrictions on objections to mining leases, very few people can now challenge matters such as impacts on groundwater of large mines that are declared a coordinated project.

A case like the recently successful objection by neighbouring graziers and others to the groundwater impacts of the massive Alpha Coal Mine can not be brought under the new system. None of the objectors in that case owned land on the mining lease or shared a boundary with it. Their main concerns were about regional impacts on groundwater.

The Minister did not explain the significance of the changes or state that the changes would reverse earlier assurances to the Parliament. In fact, he repeatedly assured the Parliament that neighbours and the general public would still be able to object to large mines.

Chris McGrath

Coordinator-General’s bad track record

The government’s assurances that the Coordinator-General can be trusted to make a proper assessment of any environmental impacts are difficult to swallow in the light of obvious lack of independence, bias for economic development, and the poor track record in this regard.

A well-known example of where the Coordinator-General botched the assessment of a large project is the Traveston Crossing Dam. The Coordinator-General recommended approval of the dam in 2009 but that recommendation was rejected by the Federal Environment Minister who refused to approve the dam due to likely unacceptable impacts on nationally threatened species.

In 2013 ABC Four Corners aired an interview with a whistleblower, Simone Marsh, who was employed in early 2010 in the Coordinator-General’s office conducting the environmental impact assessment for large coal seam gas projects. She was stunned when she was told that there was not going to be an assessment of groundwater impacts in the Coordinator-General’s report recommending approval of one of the largest projects. This was apparently done to meet tight timeframes imposed by the proponents.

As mentioned earlier, in 2014 the Land Court made a primary recommendation that the massive Alpha Coal Mine be rejected due to uncertainty about groundwater impacts. This was in spite of the Coordinator-General’s recommendation to approve the mine.

Links to federal one-stop shop

The Coordinator-General is fast becoming an almost supremely powerful czar for large projects in Queensland, subject only to the political whims of the state government.

Under the federal Coalition’s one-stop shop the Coordinator-General is also proposed to have power to approve projects impacting on matters protected under federal environmental laws.

Mining coup reflects wider trend in Queensland

Rob McCreath, who owns a farm on Queensland’s eastern Darling Downs, summarised the effect of these changes well:

It feels as if there’s been a takeover of the Government by the mining industry. It’s a bit like a coup – it’s not a military coup, it’s a minerals coup.

![]() More widely, the changes reflect Tony Fitzgerald’s recent comment that power in Queensland has been transferred to “a small, cynical, political class”.

More widely, the changes reflect Tony Fitzgerald’s recent comment that power in Queensland has been transferred to “a small, cynical, political class”.

Chris McGrath, Senior Lecturer, Environmental Regulation, The University of Queensland

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Numerous government decisions were taken over the past few years that would either constrain the CSG industry or allow it to expand

Assisting the industry are an army of former political staff and former politicians, many of whom had a role in the regulation of the industry before jumping the fence to industry. A few have come back the other way, moving from senior jobs in the major gas companies to senior advising roles in ministers offices.

The accompanying graphic reveals the extent of cross pollination between those who set policy at a state and federal level in the coal seam gas industry and those who seek to profit from it – as direct participants or as advocates for the companies.

Lobbing from the shadows

But there are a myriad of informal relationships that are less obvious to those being lobbied and to the public at large. These long standing personal relationships work to ensure a company can pick up the phone to a politician or adviser in the office if there is an issue at hand or a meeting is needed.

Take for example, AGL Energy, one of the two biggest players in CSG in NSW.

AGL tends to favour in-house representation in its dealings with politicians. The current head of government relations is Lisa Harrington, who was until 2013 a senior adviser to Mike Baird. She replaced Sarah Macnamara at AGL, who went back to work in the Prime Minister’s office with her old colleague Peta Credlin whom she knew from her days in Communications minister, Helen Coonan’s office.

CSG industry hires well-connected staffers

Despite forecasts of falling demand for gas in NSW, the push for further commercial exploitation of coal seam gas (CSG) in some of the state’s richest agricultural areas is about to regain momentum following the NSW election.

Even though the Australian Energy Market Regulator says there is now no supply gap in NSW and demand for gas will fall 17 per cent by 2019, the CSG industry is preparing to step up its efforts, arguing that the issue is now one of “energy security” for NSW .

Vested interests

Numerous government decisions will be taken in coming months that will either constrain the CSG industry or allow it to expand. There’s currently a freeze on new exploration licences that will be replaced with a strategic release framework, new codes and conditions are being finalised, and CSG will soon be regulated by the Environment Protection Agency. The NSW government also plans to have a “use it or lose it” regime for licences. It has decided not to appeal against an overturning of its suspension of Metgasco’s gas drilling licence near Lismore.

Assisting the industry are an army of former political staff and former politicians, many of whom had a role in the regulation of the industry before jumping the fence to industry.

A few have come back the other way, moving from senior jobs in the major gas companies to senior advising roles in ministers offices.

The accompanying graphic reveals the extent of cross pollination between those who set policy at a state and federal level in the coal seam gas industry and those who seek to profit from it – as direct participants or as advocates for the companies.

Green’s MP Jeremy Buckingham says the revolving door between politics and the mining sector has utterly undermined the community’s faith in our ability to regulate mining and CSG.

“It’s very concerning to see a decision maker who helped to create the industry now spruiking it,” he says.

As an advocate for an “an association or organisation constituted to represent the interests of its members” – Galilee was free to move from advising the government one month to representing the industry the next.

Those who encounter Galilee say he is very professional in the way he deals with politicians who once would have sought his counsel.

But there are a myriad of informal relationships that are less obvious to those being lobbied and to the public at large. These long standing personal relationships work to ensure a company can pick up the phone to a politician or adviser in the office if there is an issue at hand or a meeting is needed.

Take for example, AGL Energy, one of the two biggest players in CSG in NSW. AGL tends to favour in-house representation in its dealings with politicians. The current head of government relations is Lisa Harrington, who was until 2013 a senior adviser to Mike Baird. She replaced Sarah Macnamara at AGL, who went back to work in the Prime Minister’s office with her old colleague Peta Credlin whom she knew from her days in Communications minister, Helen Coonan’s office.

Macnamara was Abbott’s policy adviser on resources for a year and is now chief of staff to the federal minister for industry (and resources) Ian Macfarlane. Shaughn Morgan, AGL’s manager of Government and external affairs, has similarly impressive credentials on the Labor side. He was an adviser to NSW Attorney General Jeff Shaw in the 1990s and worked with Adam Searle, now Labor’s NSW resources spokesman.

Morgan also has connections with another important constituency for the CSG industry – farmers – having been CEO of the NSW Farmers’ Federation for four years.

And Senator Coonan is still not far from the action. The firm she co-chairs with former Labor minister, John Dawkins, GRA Cosway is listed on the Federal register of lobbyists for AGL.

Santos, the other major player in CSG in NSW has tended to employ staff from Coalition ministers’ offices and also uses external lobbying firms.

Robert Underdown, manager group government and public policy joined Santos in 2009 after five years in federal resources minister Ian Macfarlane’s office that spanned government and opposition.

The manager public affairs, Matthew Doman, had stints in Liberal minister, Nick Minchin’s office and with National leader, Mark Vaile, before joining Santos.

Conflict or public interest

“The community feel that often it’s just a foregone conclusion and that the government is paying lip service to regulation”.

The Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration, the coal seam gas industry body, declined to comment when contacted by Fairfax Media.

Often politicians and political staffers jump directly into a role that involves them advocating for the companies, unrestrained by rules that are designed to provide cooling off periods between politics and business.

For instance Martin Ferguson, the former Labor resources minister, became chairman of the advisory committee for the peak oil and gas industry association, the Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association, six months after leaving politics.

He has been a fierce advocate of CSG, arguing that NSW must forge ahead with development of CSG in order to achieve “energy security for NSW.”

His colleagues, Greg Combet, the former Gillard government minister for Climate change and Craig Emerson, her minister for Trade, waited a year before penning an opinion article in support of the CSG industry in the Australian Financial Review.

They are both working as economic consultants to AGL and Santos, the two biggest players in CSG in NSW.

Former National party leaders, John Anderson and Mark Vaile also moved into high profile roles in mining and CSG companies after politics. John Anderson became chairman of Eastern Star Gas, the company behind the Narrabri Gas project about two years after leaving politics.

Mark Vaile became a director and then chairman of Whitehaven coal, the company behind one of the state’s most controversial mines at Maules Creek. He is regularly seen in the corridors of Macquarie Street.

There are state and federal rules that impose cooling off periods for politicians and senior bureaucrats who move government to lobbying, but the act of lobbying is defined very narrowly to prevent only “gun for hire” third party lobbying. This leaves politicians free to take jobs at industry associations and in business. In NSW minister must seek advice from the ethics adviser before taking private sector jobs.

The most high profile shift between politics and the mining industry has been Stephen Galilee, who is the former chief of staff for then Treasurer, Mike Baird. Galilee moved soon in late 2011 to become chief executive of the NSW Minerals Council.

A spokesman for the council said it does not lobby on the gas industry – it leaves that to APPEA – but it is intimately involved in all things mining including the planning and environmental regimes.